Why we obsess over people we’ll never meet

The word “celebrity” almost instinctively lends itself to visions of glamorous models, mansion-dwelling musicians, and questionably talented actresses, all of which are recipients of immense fame and wealth. However, our current perception of celebrity has not been consistent throughout history. The word itself derives from the Latin word “celeber,” meaning “frequented or populous.”

In Ancient Rome, original celebrities included gods, whose fame was enhanced by the creation of myths by admirers who sought to personalize these idols. While monarchs and civic leaders achieved a degree of fame, gods surpassed these individuals in recognition. It was also during this era that individuals began to idolize athletes, victors of the Olympic Games and gladiators for their strength.

With the Dark Ages’ increased influence of religion, monarchs began to reach greater status; martyrs, saints and other religious figures achieved newfound fame. However, the lack of widespread literacy only allowed fame to spread through word of mouth, lessening its permanency.

As the arts flourished during The Renaissance, sculptors, painters, and artists acquired greater popularity than civic and religious figures, a trend that arguably continues to this day in some form.

Mass, lasting celebrity status like we see today was not achieved until the rise of the printing and publishing industries, which resulted in increased literacy rates during the late eighteenth century. By the twentieth century, the advent of film, television, and radio allowed actors and athletes to achieve widespread fame.

As social media and reality television allow individuals of questionable talent to achieve enormous fame, the question remains why we worship certain individuals over others and what it really takes to reach celebrity status. The answer is difficult and uncertain, though various theories have presented themselves.

Writer Jake Halpern, author of Fame Junkies: The Hidden Truths Behind America’s Favorite Addiction, which investigates America’s obsession with the lives of celebrities, argues “there are a confluence of factors” to explain our preoccupation with celebrities. One factor, he suggests, is evolutionary.

He then presents the prestige theory, which is “the idea that over time, people that could find alpha males in their group and either learn from them or ingratiate themselves to them stood a better chance of surviving and having offspring, which is a key for an evolutionary trait.”

“In a way,” Halpern continues, “this argument posits that over time, there would be a gene or kind of trait, and that trait would be in some way a kind of star-gazing, celebrity-worshipping type trait, where you’re admiring, learning from, and gravitating toward people who are powerful or have skills that can teach you something.” While Halpern recognizes society has significantly evolved, he argues the impulse to gravitate towards celebrities remains.

Another theory Halpern postulates derives from the research in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, written by Robert D. Putnam. The book explores data stating Americans are lonelier than they’ve been in the past; they live alone more often and families are smaller than they have been traditionally. As a result, Halpern argues individuals form a relationship of sorts with celebrities, classified by psychologists as “parasocial” relationships. “They follow the celebrities and these magazines like Us Weekly kind of plan it out and target celebrities on a first-name basis — like Brad, Ben, and J-Lo.”

While many will agree our society overemphasizes the importance of celebrity, whether the effects of celebrity adulation are detrimental is subject to debate. Most individuals’ admiration of celebrities is reasonably healthy, but others suffer from what psychologists call “celebrity worship syndrome,” an obsessive addictive disorder in which individuals, to the detriment of their mental health, become desperate to unearth the details of their idols’ lives.

Originally coined in 2003 by The Daily Mail writer James Chapman, the term referenced the celebrity worship scale originally published by Dr. John Maltby and colleagues in “The Journal of Mental and Nervous Disease.” In contrast to earlier research on “celebrity worship” conducted by Dr. Lynn McCutcheon in the early twenty-first century, Maltby and his colleagues described three independent dimensions of celebrity worship — entertainment-social, intense-personal, and borderline-pathological.

The first dimension relates to a celebrity’s perceived ability to entertain and socialize; the second to compulsive attitudes regarding a celebrity; and the third to individuals with uncontrollable behaviors and desires relating to said celebrity. Further studies indicate correlation between pathological characteristics of celebrity-worship syndrome and high anxiety and stress levels as well as poor body image.

However, the negative effects of celebrity are not limited to those who fervently worship their celebrity idols. The objects of idolization can be equally affected. In rare cases, one’s obsession with their idol may become violent. Noted examples include the murders of musician John Lennon and actress Rebecca Schaeffer by deranged fans.

According to psychologist and author of Confusing Love with Obsession: When Being in Love Means Being in Control, John D. Moore, celebrity worship can become problematic. “Generally speaking, when the person becomes consumed with another person to the point where they start to stalk them, there is a potential for something bad happening.” He argues when stalking no longer fulfills their desires, and obsessed fans discover a stark contrast between fantasy and reality, “it can cause an unwanted response… sometimes this can mean violence.”

While Moore states that worship of celebrity “can be a sign of a delusional disorder,” and individuals with “very low esteem or self-concept” are particularly susceptible to stalking behavior, others argue the media’s crucial role in celebrity obsession. Many cite books, diets, food, jewelry, and other material items advertised to consumers as possessions that may help individuals achieve standards set by their idols. With the rise of social media and subsequent ascendancy of its stars, such standards are now worryingly created behind the facade of Instagram or Twitter. Nora Turriago, a regular contributing writer for The Huffington Post, believes the constant coverage of celebrities leads more young adults to view fame as a viable life goal. “They see people their own age, or even younger, who are living a very attractive lifestyle. And these are famous people who don’t even have a particular talent or skill… it seems to require no special gift or ability.”

Despite the troubling, sometimes violent examples of celebrity worship, positive examples of its benefits do exist. Many celebrities use their fame and fortune to visibly support charitable causes, as did actress Brooke Shields when she sought to raise awareness of postpartum depression. Reality shows such as “The Apprentice,” are credited by some viewers with encouraging them to achieve their dreams. While Jessica Radloff, contributor to Glamour magazine, concedes that while idolization of celebrities has negative effects, she nonetheless argues it has some positive benefits. “We’re moving away,” she states, “from celebs that often seem so unattainable…. to those that are not afraid to admit they are complex and going through things like anyone else. No celeb is perfect, but now the conversation is moving towards embracing the ‘real’ and not just the facade that we often saw decades ago.”

As for many individuals’ complaints that social media, reality TV, and other hallmarks of modern celebrity are ruining America? Halpern argues “there was an element of American culture that was always pretty slapsticky and silly… I think there’s just a part of a human being that loves stupid humor and silly, stupid stories. And I think that, in a way, there’s nothing wrong with that.” He warns potential danger can arise when celebrity worship seeps into one’s everyday activities. “Entertainment creeps into the realm of news, so that you go to a news place that you typically rely on getting hard news and instead, they’re kind of covering soft celebrity stuff.”

Turriago expresses similar views. “Even established news outlets like The New York Times and CNN write about the latest celebrity updates.” She considers this phenomenon to be evidence that such news outlets are “either trying to expand their reader base and, most importantly, the celebrity craze has become such a crucial fixture of our society that not reporting it would be ignoring a powerful group of influencers.”

As Radloff points out, our focus on celebrities is not necessarily bad. While others may argue the incessant coverage of celebrities hinders society from focusing attention toward “real” issues, she notes that there are plenty of resources available to get news and information 24/7. And for those who want to preoccupy their time in other ways, “it also helps to have the lighter celeb moments in the wake of what seems like a 24/7 dire news cycle.”

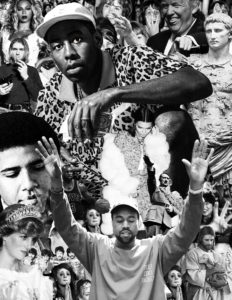

Today, in an era where violence and poverty are ingrained into our everyday lives, one cannot deny the likability of such tender moments as Beyonce and Blue Ivy wearing matching mother-daughter outfits, or North West skipping to ballet class. Maybe the ancient Greeks who enjoyed the Olympic Games realized something we as a society have yet to — we idolize these individuals for their ability to make us laugh and cry. We rely on celebrities in order to transport ourselves into a fantasy far less dreary than our reality. While our obsession with them may go too far, one cannot deny that by tapping into the parts of the human soul that beg to be touched, celebrities perform an essential role in society.

Mattie Beauford is a first year writing major who thinks Perez Hilton is a credible journalist. You can email them at [email protected].