A look at one man’s transformation of the local education system

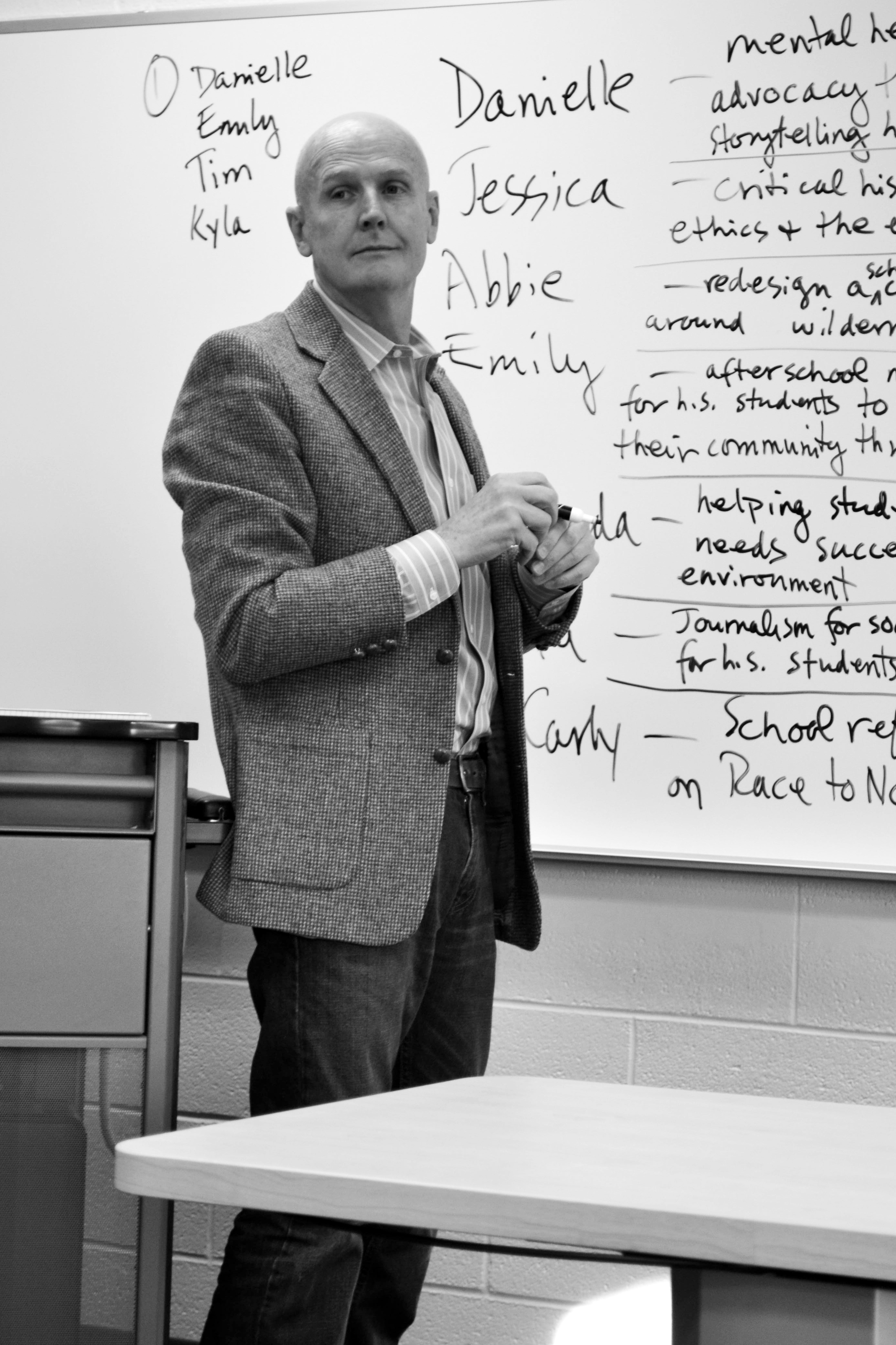

Photo by Amanda Kirschenbaum

It was a Friday afternoon in late May, just a few weeks before the school year would end and students would be huddled on curbsides waiting for ice cream trucks to make their hourly rounds.

But for one teacher, six weeks was too long. That afternoon, she turned in her keys and her grade book. “I won’t be in on Monday and I’m quitting teaching — and that’s that.”

Enter Mr. Jeff Claus: a curly headed graduate student of the University of Pennsylvania who had been substitute teaching at the school for the semester. That same afternoon, the Principal of the predominantly low-income,minority-populated school called Mr. Claus into his office and made a proposition.

“How would you like to finish out the year here?”

While a two-month salary was an attractive option, Claus worried that his focus on teaching English would disqualify him from filling the school’s need for a math teacher. No sooner did the principal reassure him: “All you have to do is tread water.”

“This was my first example of inequality,” Claus said.

As an inexperienced college student, not even finished with his Masters degree, Claus was placed in a situation where kids were going to be lied to. The previous teacher had already decided to fail some of them, which meant those students would be held back the next year.

“[The principal] treated this as fine, normal and acceptable,” Claus said.

For Claus, prior teaching experience helped reveal the types of institutional suffering that take place when kids are placed at the hands of a system that doesn’t respect them.

“As part of that experience, I became interested in the fundamental inequalities and injustices that African Americans experienced in schools,” Claus said.

Ithaca College welcomed Claus to the Education department in 1994. Since then, Claus has focused his teaching on social and cultural issues in education. To begin combating these issues of race and racism in education, Claus believes public education needs structural change from within — and that begins with teachers. His pedagogy has been “to support and foster the development of educators who will have not only the skills, but also the persistence and the courage and the resilience to work within an institution of public education.”

One of Claus’ former students, Erin Irby, said she has always been passionate about education. In fact, she may be destined for it — both her parents are teachers. As a senior on the cusp of graduation, Irby is planning to apply for a teaching assistant position in France. She’s pursuing this option in part because of her study abroad experience in Toulouse this spring, and in part because of Claus’ pedagogy. Her experience in his course allowed Irby to critically examine the public education system both at home and abroad.

“They created the French education system to unify the nation with a common language, but bridge the gap from aristocracy and peasant population,” Irby said in reference to Horace Mann’s notion of education being “the great equalizer.” Mann believed education was the “balance-wheel of social machinery,” giving each person the independence and the means to resist the selfishness of others and the poverty that creates achievement gaps.

Claus, however, helped Irby break down this misconception and think critically about the institutional structures enabling privilege and disenfranchising marginalized groups. She said Claus fostered this critique by encouraging students to share their stories and personal experiences in education, never imposing his own views on their discussions and ideas.

“For future educators it’s very important to have a good educator, and he was the epitome of that,” she said.

In his courses, Claus also uses interviews from his own research to illustrate the need for multicultural and culturally affirming education, and demonstrate the consequences of schools that fail to do so. Senior Liz Stoltz, who took Social and Cultural Foundations of Education her freshman year, said Claus stimulated her energy to research the impacts that poverty and adequate nutrition have on educational opportunities.

“I was encouraged to examine more critically how socioeconomic status correlates with school funding inequities and nutritional deficiencies,” she said.

Only months into her first year at Ithaca College, Stoltz launched the campus organization Food for Thought, which aims to provide education and charity for communities dealing with children’s malnutrition across the globe. For the past few years, Stoltz has also been a student researcher for She’s the First, an organization that sponsors girls’ education in the developing world, helping them become the first in their families to graduate.

“Through our research assignments, he influenced my advocacy for treating school food as a social justice issue,” Stoltz said.

As the first faculty in resident of the Martin Luther King Jr. Scholar Program, Claus has left a legacy. Integrating his love for education and social change, Claus guided the scholars through their research and social justice projects. During a social-justice trip to Ghana, Claus and the MLK scholars and faculty visited the “slave castles,” where slaves were held before being shipped to the United States. In social-justice and international spaces like these, which have been designed with the purpose of educating people about what happened there, Claus said his position as a white, middle-class male was moving.

Upon leaving the site and returning to the bus, many of the MLK students and faculty members were solemn. One of the sophomore scholars began reconciling her feelings about her own identity — having an African-American father and white mother: “I never understood my father until this moment.”

As Claus restated her quote, tears began to well in the ducts of his eyes, reenacting his own thoughts and emotions at that time. “As an educator, with a critical perspective on schools, I thought, ‘What a failure of the educational system.’”

Claus believes identity crises for students of underrepresented groups illuminate how our school systems hardly provide educational experiences that are intellectually truthful and rich about experiences around race and racism, and that are also emotional.

“We don’t take people to emotional places through learning when we should,” he said. “We avoid all of that.”

Music is a personally emotional and creative outlet Claus uses to help people understand one another. Roger Richardson, creator of the MLK scholar program, said Claus often integrated musical and cultural elements into the MLK Program’s travel trips or discussion series to illuminate how rhythms and lyrics can carry emotional and moving social-justice narratives.

Claus also fuses his passion for music and social-justice learning on the community level. As a longtime guitarist and lyricist, Claus has enjoyed performing with his wife, Judy, in both the major label group The Horse Flies and indie rock band Boy With A Fish. As a testament to Claus’ integration of music and rights-based narratives, both local bands were affiliated with Artists Against Fracking. While Claus tours locally and abroad with the groups, he also works with his wife on film scoring. The couple will begin their newest project in January, shortly after Claus’ retirement, scoring music for Northern Borders, a film based on the book by Howard Mosher.

From hosting community dinners at his house to engaging students in service projects at local elementary schools and community activity centers, Claus has set the bar high for other faculty members at Ithaca College. According to Richardson, he models the behaviors that any committed faculty has in terms of his or her scholarship, and the application of that scholarship in terms of the lives of people.

Addressing the MLK Program specifically, Richardson said, “He’s someone I’m indebted to for his willingness and commitment to wanting to make a positive difference in the lives of these talented, underrepresented students.”

Richardson has also observed Claus actively working to change the lives of youth outside the classroom. For the past 10 years, Claus has been involved with the South Side Community Center. He wrote the grant that funded the center’s radio program, which has become an important social medium for educators and social-justice leaders like Claus to reach and connect with young people.

While Claus is leaving the top of South Hill come December, Richardson believes his engagement with the Ithaca community will continue fostering the relationship between academia and community, and serving as a “premier ambassador” for creating the next generation of individuals who can use education as a way of social mobility — regardless of where the learning occurs.

“What we lose is a practitioner in addition to a scholar,” said Dr. Richardson. “What we gain is someone who will be an advocate in the community who will allow the community to continue connecting with college.”

Megan Devlin is a junior CMD major major who may not be filling the gap, but could mind the gap if she moves to London. Email her at mdevlin2[at]ithaca[dot]edu.