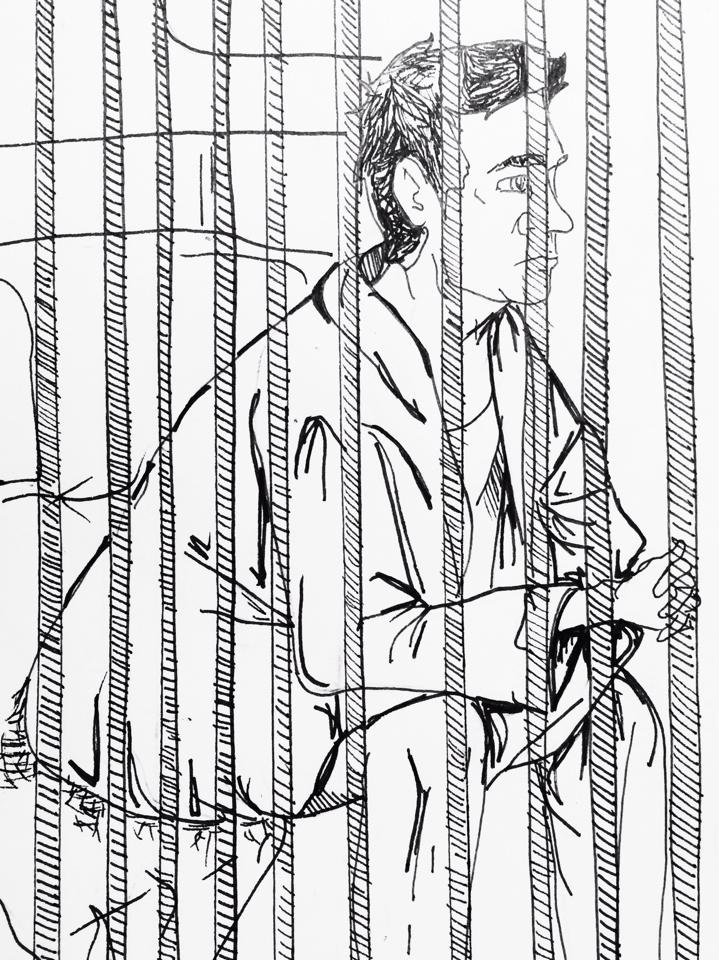

Image by Georgie Morley

Open glass windows and soft brick walls line the hallways of Norway’s Halden Fengsel. Bedrooms are laid out with flat-screen TVs, mini-fridges, private showers and toilets, and the smell of baked goods from weekly culinary classes often wafts down the corridors. But Halden Fengsel isn’t a trendy, new hotel or high-class university building. It’s actually a prison.

In 2010, the King of Norway unveiled one of the country’s largest maximum-security prisons, which holds up to 252 inmates and cost a whopping $280 million to open. To hold one prisoner in Halden costs the state around $192,000. Compare that to the state-by-state range in the United States of $14,000-$60,000 per year, and it’s easy to see how such amenities can be afforded. So why do Norwegians want their tax dollars to pay for rapists, murderers and pedophiles to have recreational jogging trails and a state-of-the-art sound mixing room?

Intertwined in Norway’s unique justice system is the fact that no criminal can get more than 21 years as a sentence. And knowing that the majority of prisoners will one day have to immerse themselves back into society, Halden’s governor, Are Høidal, would rather offer therapy than punishment.

“If you stay in a box for a few years, then you are not a good person when you come out,” Høidal told the Guardian. “It is this building that makes softer people.”

Arguably, the most important reason countries like Norway pursue more therapeutic methods within their penal systems is because they see a consistent decrease in recidivism, or the behavior which causes ex-convicts to return to jail.

So if a happy prison equals happy inmates, and in turn eliminates jail violence and decreases recidivism, why don’t any so-called “luxury” prisons exist in the US?

According to a 2011 study by the Pew Center on the States, the US incarcerates more people per capita than any other nation in the world. In 2010, a total of nearly 7 million people (more than the entire population of Norway) were either behind bars or under correctional supervision in the “land of the free.” And that isn’t because of higher crime rates.

The US imprisons a lot of types of criminal offenders, including non-violent and drug offenders, and has a sentencing system that allows for little leeway in terms of jail time. Moreover, when some of those 7 million Americans get released, more than 4 in 10 are expected to return to prison within three years.

So, who should care that people who commit crimes are being sent back? Actually, anyone who pays taxes should. As it turns out, doing something as mundane as attending school behind bars reduces recidivism from 40 percent to 10 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Education. It can save Americans a lot of money, says (NY) Gov. Cuomo, who announced an initiative in February to provide college courses to prisoners at 10 out of 58 New York prisons.

“Giving men and women in prison the opportunity to earn a college degree costs our state less and benefits our society more,” Cuomo said.

New York State currently spends $60,000 per year on each prisoner in its system, and past programs show that the $5,000 used to educate each inmate would allow men and women to restart their lives outside of jail instead of returning. And with fewer prisoners in the cycle of recidivism, residents would see a decrease in tax dollars owed to the state.

Assemblywoman Barbara Lifton agrees with the initiative, but said that unless the Governor pushes hard enough, there is a low chance the program will pass.

“We actually have a budget deficit of $2.7 million, so there’s actually no money to spend, no matter how much we might support these programs,” Lifton said.

In the meantime, some maximum-security prisons like the nearby Auburn Correctional Facility, allow inmates to organize visits with organizations who provide recreation and therapy to prisoners.

Junior Blaize Hall is a member of the local Phoenix Players Theatre Group, which travels to Auburn once a week to practice for a theatre production that will involve 6 inmates and a group of community members. After experiencing a show her freshman year, she was so moved by the self-awareness and profound grief expressed in the inmates that she knew she had to be involved.

“You go in not knowing what to expect, nervous as to how the guys will receive you, if they’ll like you, if they’ll make me uncomfortable, and you meet the sweetest, most personable guys ever” Hall said. “And these guys are smart—the material they write and bring to class to perform is such high quality.”

The Group, facilitated in part by Judy Levitt, a theatre instructor at the college, has a similar intention to that of Norway’s Halden Fengsel prison, which is to help prisoners not only find purpose, but also themselves. Levitt has experienced the transformation of many during her time at Auburn and says the therapeutic value is enormous.

“They’ve gotten back in touch with their humanity and have found out who they really are,” Levitt said. “And they really want to spread the message outside the prison that this is a place with human beings that can accomplish something and can be valuable to society again.”