This year, we look forward to many anniversaries, one in particular being the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck’s novel is considered one of The Great American Novels, and in the midst of those good reminiscent feelings anniversaries provide us with, it is only right of me to deliver some contrast; The Grapes of Wrath is sort of a rotten pick for the title.

My main line of thinking is not so esoteric: the Steinbeck novel is not great, but it is embarrassingly American, as all picks for the Great American Novel seem to be.

Let’s break it down. The Great American Novel is generally considered to be a novel set in the United States. that embodies the essence of this country and its condition. Critics’ use of the term has dictated what American novels examine and what it means to adopt the American condition.

I am not in pursuit of what The Grapes of Wrath specifically has accomplished. Instead, I seek to discern what The Great American Novel says about us as a people and what it should say.

Although Blood Meridian is turning 39 years old this April – an anniversary rarely celebrated – I’ll round out my analysis with the Cormac McCarthy novel.

Quite frankly, any book noted as one of the Great American Novels can be similarly contextualized; this is not to review any one book. Think of your own personal copy of Moby-Dick or Infinite Jest and tuck in.

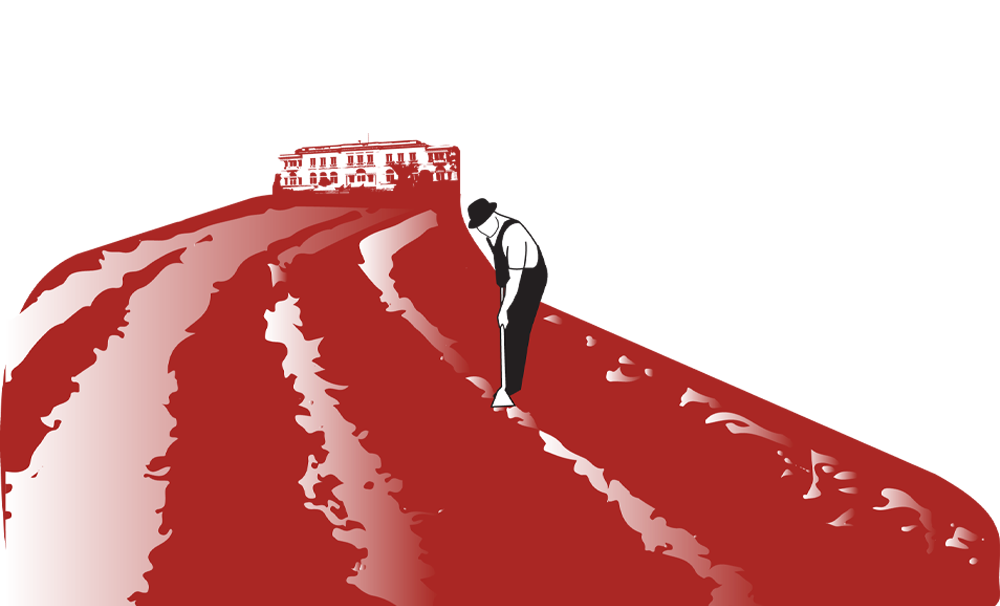

Exceptionalism has been seemingly inherent in American culture, but it is a misstep to equate America with exceptionalism. The Grapes of Wrath does it by buying into the idea that these “Okies” are escaping the Dust Bowl as migrant farmworkers in search of proletarian collectivism. In America, these people are the backbone of political conservatism and were mostly urban migrants. This history often fails in the face of poetry as hardship. The story ends when the Joads leave the fields because unmistakably, a darker family took their position for far less and stayed impoverished far longer.

Directly after the Depression, there was a huge boom of white male wealth, the Joads most likely benefitting, and the narrative of white victimization fell apart. Even as the book was being sold, the conditions of white people were greatly improving. The purpose of this book was to preach. Preach what? Plight. If this is something you can even do, Steinbeck accomplishes it.

Does America really concern itself to this degree with the condition of being American? Of course it does, but not in this order. Alas, exceptionalism will have its way with American audiences. If I know anything about the white American condition, it’s that it so often perceives plight as absolute.

Blood Meridian is a tale of white and Mexican men profiting off of their violent instincts by killing indigenous tribes and scalping them.

With Blood Meridian, you find this exceptionalism in the novel’s relentless violent prose. In comparison, this is not necessarily a story of whiteness, instead it is a story of nature. The issue with reading a novel written by a white man of this magnitude is that there is an absolvement of guilt just by writing it at all.

This is really where exceptionalism falls into place for a semi-aware America: (semi being a generous descriptor) in preaching and guilt. But that isn’t the story of America, that is the story of white America, of blind America, of history as written by the “victors”.

In the storytelling alone, you see the un-regulation that privilege allows. This meandering epicness fails in every way to be whole. Hats off to you McCarthy, I’m referring to your painful lack of dialogue.

As epic as navel-gazing gets, as epic as the detangling of exceptionalism feels, these examples are all contrived. The structure of the writing alone is indicative of this, let alone when you analyze the stories themselves.

In the same swing though, these novels aren’t gormless. These stories, just like many others, deserve to be told, and white authorship is decidedly no less important than other authorship.

The Great American Novel is not held by one book, there is no monolithic greatness in American literature. Why then, is The Great American Novel a title belonging to so many similar ideals and narrative purposes?

The America we know is admittedly exceptionalist, but there is no grandeur to the hardship and heterogenous livelihood of its people (even if many white people can afford to see it that way). The Great American Novel deserves much more than to limit itself to what white America has been or what it has stood for.

We should be looking at indigenous work, women’s novels, black and Chicano fiction, and all the other marginalized communities that are glaringly absent from these lists. If this somehow finds itself in the hands of a literate bigot, don’t worry! I am not looking to rob you of that sweet sweet male white authorship.

Keep these titles around, revel in them, but also, want more. There are many other stories that contribute far deeper and kinder to America as it exists in greatness. These are important stories, those are the real Great American Novels.

Maggie is a second year writing major who wants to deconstruct the idea of The Great American Novel. They can be reached at mchilders@ithaca.edu .