More Than Just a Trigger Warning

The myth of the safe space seems to be perpetuated across media outlets more and more in recent years. Images of weeping college students in bean bag chairs cuddling service dogs are the perfect caricature of liberal snowflakes who can’t handle the slightest brush with controversy. It’s a tempting generalization, but the history of safe spaces runs much deeper.

The origins of the term are disputed among historians. It first came into wide use within the LGBT community in the 1960s to describe gay bars and other locations where people were free to be themselves without police scrutiny. Second Wave Feminists also created safe spaces where women could speak freely about their beliefs, and in many cases, escape domestic violence. Labor unions aimed to create safe spaces where employees could freely critique their managers without fear of being fired. Over the decades, the term came to be associated with any place where marginalized communities can gather in solidarity. What we have continuously seen in recent decades is that the violation of safe spaces is deeply destabilizing. This can be traced back to the Stonewall Riots, but we’ve seen it in the mass shootings at a black church in Charleston and the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

Before Ithaca College’s Center for LGBT Education, Outreach, and Services was founded in 2001, students actively worked to create designated safe spaces, using their own money to print the stickers that are now a common sight around campus. The program was standardized with the founding of the LGBT Center and efforts began to turn the idea of safe spaces into official college policy. Director Luca Maurer has worked for the Center since 2001. His job includes collaborating with students to ensure a diversity of perspectives are accurately represented within the college and that faculty are adequately trained to make their classrooms a learning environment where people of all identities feel welcome.

“A safe space only works as long as everyone in the space agrees to certain expectations,” said Maurer. While many departments have been responsive to professional development training, Maurer admitted that there have been times when people have invited him to give presentations on “LBGTQ issues”; when he pressed for more specific details, they expressed that anything he came in and said was fine.

“These are well-meaning people. I don’t want to cast them as bad people. What they are thinking of is using my expertise to check a box. Checking a diversity box is not the same as acting in solidarity…The point isn’t to claim you’re a nice person, the point is to create a campus culture where students can be who they are and do what they want.”

The Department of Theatre Arts has long been considered the definitive safe space at Ithaca College, according to department chair Catherine Weidner. “There never used to be an LGBT Center; the LGBT Center was Dillingham,” said Weidner. “Things still happen of course, because we’re human, but I think that Dillingham has always been a place where people could be themselves.”

As a graduate of the Class of 1980, Weidner has seen the campus radically change into a place where students feel increasingly comfortable opening up when their safety feels threatened. “It’s important to be able to walk into a room and feel like you have agency and that you’re making a contribution,” she said.

In an area of study where confronting highly-charged topics is often a typical part of the school day, the discussion of safe spaces is constantly evolving. Within the department, Weidner believes that professors should be responsible for informing students when material may be in violation of the idea of a safe space. “In classroom I think there’s an understanding that the work is challenging, and that you’re going to be asked to read novels and plays, and students have the right to say ‘I found this offensive, I found this is erasing my experience,’ and I don’t think we should be shutting down that conversation.”

But Dillingham Center has the unique position of having obligations to the wider Ithaca community, as often times they are the customers that fund the theatrical productions. Health hazards like strobe lights and haze are both advertised on signs in the lobby before shows and posted on Facebook. A recent production of Henrik Ibsen’s 1891 play Hedda Gabler featured an extensive program trigger warning, informing the audience that the production would include, “bullying, humiliation, alcoholism, sexual harassment and assault, and suicide,” as well as “the use of non-firing handguns.”

Weidner, however, is not convinced that these initiatives align with the goals of theatre as an art form. “You come to the theatre to be offended, entertained, and shocked. We’ll tell you it’s not for kids under 13, but we’re not going to go into a laundry list anymore…the truth is theatre is about making us uncomfortable.” Health hazards will continue to be advertised under the term “audience advisories” rather than trigger warnings.

Dr. Patricia Zimmerman, Professor of Screen Studies in the Park School, shared similar sentiments. Film studies as a discipline has always shied away from trigger warnings, and they are outright forbidden in Ithaca’s department. Health accommodations are processed through Student Accessibility Services, but it is up to the individual student to research the films prior to screenings to see if material will be triggering.

“Part of the role of media and cinema and art is to, in fact, disturb, and then to open space for dialogues about all of this, not shut down dialogues,” Dr. Zimmerman elaborated. “I have had students tell me they need trigger warnings because a film on the partition of India, which was a bloody genocide, ‘disturbed’ them. My response is this: It should disturb you. Genocide is a crime.”

She also cited the global extent of film studies, explaining that the idea of trigger warnings is an inherently American construct that makes cultural assumptions about the audience. “We leave it to the student to leave if it is disturbing, but again, the point of art is to disturb the status quo, and I would never assume I could know or understand all the different cultural differences in my students.”

Both professors share the official stance taken by the American Association of University Professors, which Catherine Weidner quoted directly in the theatre department’s 2019 Season At A Glance letter: “The presumption that students need to be protected rather than challenged in a classroom is at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual. It makes comfort a higher priority than intellectual engagement.” The effects of this statement have rippled across the country. Safe Space Programs are not standardized, and there are still universities where having an LGBTQ identity is forbidden in the student code of conduct. Yale University came into the national spotlight in 2015 when efforts to ban racist and offensive Halloween costumes were ridiculed as a violation of the First Amendment.

Luca Maurer disagrees. “Saying that you welcome all different kinds of people into a space doesn’t mean you can’t say whatever you want,” he said. “Freedom of speech doesn’t mean other people can’t express other opinions, and freedom of speech doesn’t mean there may not be consequences.”

In spite of the progress that has been made and the overall student acceptance of IC’s safe space program, Maurer understands that there is still much work to be done. While the LGBT Center can offer training to staff and counsel students, Maurer does not have the authority to judicially punish those who violate safe space policies. “I could go through a training and walk out at the end and never change any of my behavior,” he said. “If someone says, for example, ‘I’m not going to call you by your correct name,’ there’s no amount of training that will stop them.”

In spite of the differing perspectives, the complexity of the arguments surrounding safe spaces shows that the issue runs deeper than handing a lollipop to a sad teenager who can’t cope with challenging topics. It is about hearing the voices of identities that have been historically silenced, taking responsibility for mistakes, and learning to think of one another’s needs in more complex ways.

“I think as long as people are willing to come to the table and have these discussions, that’s great,” said Maurer. “What I take exception to is when your disagreement with me stems from the belief that I should not be allowed to exist. To me, that’s where dialogue ends.”

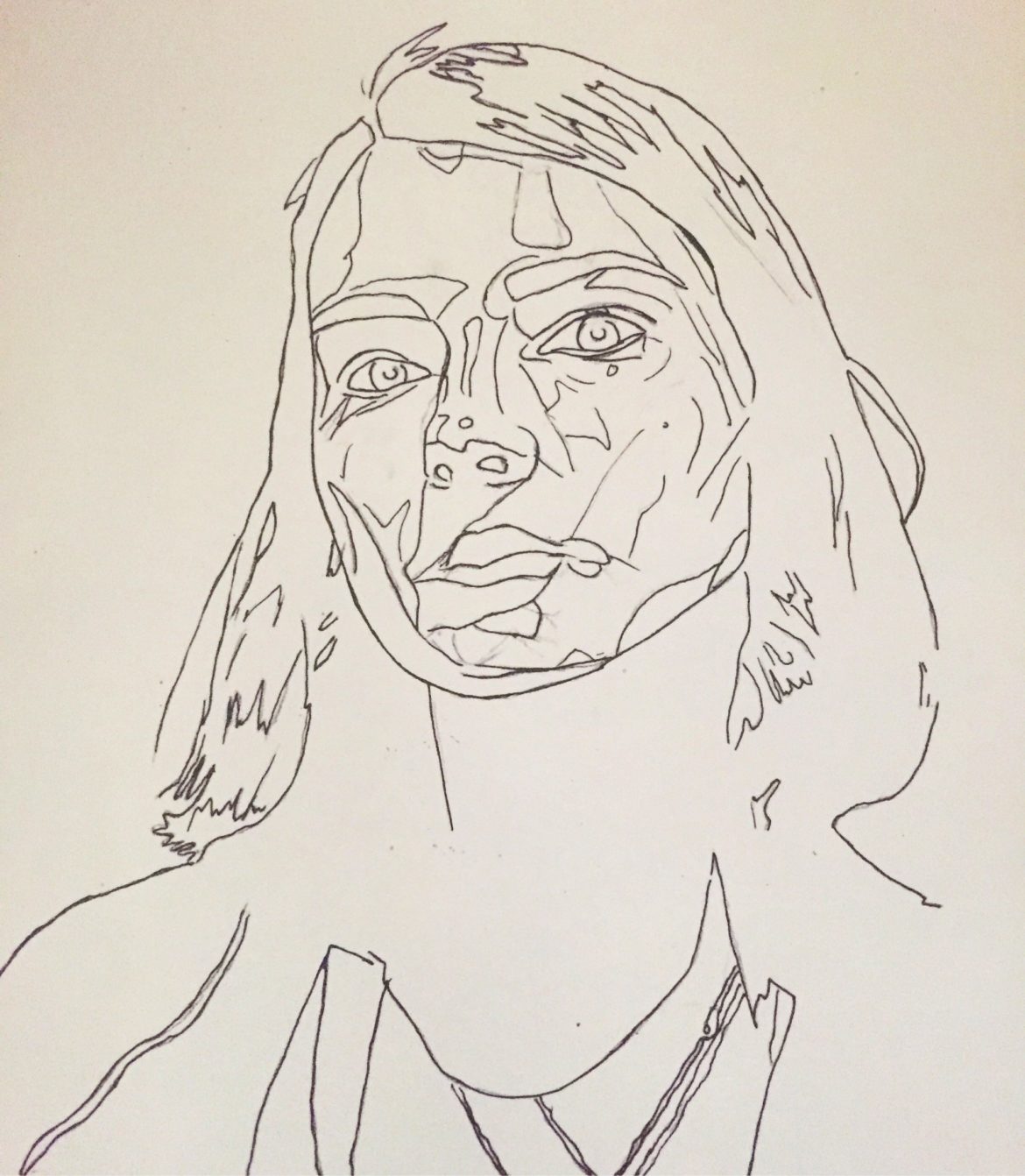

Rachael Powles is a second-year theatre studies major who hates the term “special snowflake.” You can reach them at rpowles@ithaca.edu. Art by Caitlin Breslin, Contributing Artist.