By: Tyler Obropta

The Lady in the Van commences with a smashing opening, and I don’t use the term “smashing” simply because it’s a British film. Dame Maggie Smith literally smashes her van into a person. And kills him. In the film’s first 30 seconds.

Instead of calling the police, Smith’s eponymous lady in the van takes it on the lam, living in the streets for quite some time. The broken windshield becomes a constant reminder, the damning black spot on the hand of Lady MacVan.

The brilliant Alan Bennett adapted the script from his 1999 stage play, based on a (mostly) true story. In fact, the film was shot on location at Bennett’s old home in the London Borough of Camden. It was there that the real-life Miss Mary Shepherd, the thankless and eccentric homeless woman, put her roots down in the playwright’s driveway in the 1970s.

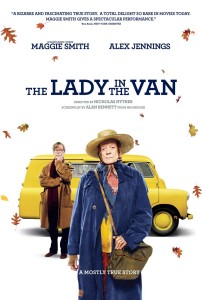

Bennett here is played by a delightfully timid Alex Jennings, who adeptly mixes the unrestricted, abrasive wit of the writer with the mild-mannered soul of the man. The playwright watches Miss Shepherd from afar as she molluscs her dingy, rusted van to numerous neighbors’ doorsteps over the course of several months.

It’s during this observational period that Bennett befriends her, more out of curiosity than anything, and it isn’t long until he’s begrudgingly allowed her to move into his drive. For only a few months, of course.

And she stayed for 15 years.

As the van-dweller, Smith revels in Miss Shepherd’s bizarreness and the mysterious daftness of a woman who’s spending the autumn of her life squatting in a smelly, dilapidated van the color of a mimosa cocktail.

For such a simple premise, Bennett writes it so elegantly, with much self-awareness and the kind of beautiful intelligence that’s so rarely found in a comedy.

Unfortunately, it puts on the brakes as it nears the third act, and we begin to squeeze some emotional backstory from Miss Shepherd, the lady in the van. There’s a tonal shift that’s pretty much universal in most modern rom-coms. While most Judd Apatow films and Hugh Grant vehicles can get away with these drama-heavy third acts, it’s mostly because those films aren’t written by Alan Bennett. In The Lady in the Van, the retreat into convention is disappointing, a betrayal of the simplicities and subtleties that made the first hour so engaging.

Of course, the writing is still sharp and the performances genuine, but the movie suddenly seems a little less willing to have fun than it did when Dame Maggie Smith was still just a woman in a van, and nothing more.