Film Review

By Olivia Blees

Contributing Writer

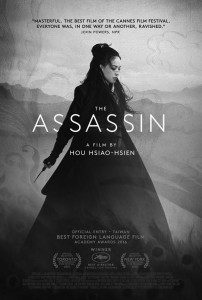

The standard Hollywood hitman is unemotional, unaffected and at some point, must deal with a target from their own past. Director Hou Hsiao-Hsien flips the script in The Assassin, and not just because the film is about a hesitant female killer in 9th-century China. This rivetingly beautiful drama considers themes of obligation, endurance, loneliness and empathy.

Taken from her family as a child and raised by the mysterious nun-princess Jiaxin (Sheu Fang-yi), Nie Yinniang (Shu Qi) has been trained to kill without question. However, she fails to slay a provincial governor when she finds him with his young son. Unsatisfied with Yinniang’s still soft heart, Jiaxin sends her after an even trickier target: Yinniang’s cousin and former betrothed, Tian (Chang Chen).

Tian manages Weibo, a secluded northern province with a developing army that threatens the emperor. Although he and Yinniang were promised by their parents when they were young children, this was more a family treaty than a romance. All the same, Yinniang is unwilling to assassinate Tian. She bides her time, learning and considering her task. During a black-and-white scene the audience is introduced to the killer Yinniang as she slits the throat of a man while he’s on horseback. The next shot is not of spouting blood, but of falling leaves, a traditional symbol of transience, distinctive of the Taiwanese filmmaker, who was awarded the prize for best director at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Cinematically, one of the most prominent things about Yinniang is her weapon: a short, arched dagger. Yinniang dispatches treasonable government officials with a blade meant for quick jabs, not drawn-out duels. There are no classic sword fights in this film: the violence is swift and short-lived.

The draw to most of these Chinese martial arts films (wuxias) is their action scenes. Hsiao-Hsien still deals with that in The Assassin, but his focus on schematic violence is purposely annoying, presenting quick shots of huge kung-fu fights on wire-work filmed behind dense forests from a distance, or centering on one character’s reaction with sword fighting in the background. These scenes often stop as suddenly as they start, and Hsiao-Hsien doesn’t offer easy background for many of them. One would almost assume the wuxia genre substance was something he was hesitant to add to tell this story, if the sense of obscurity and stillness didn’t also feel deeply purposeful.

In his own way, Hsiao-Hsien created the anti-wuxia film in The Assassin, implementing the same directorial control in sword-swinging battle as he does in catching the historic melodrama that progress. As with the stoic Yianning, Hsiao-Hsien’s tactic finds beauty and secrecy in the fixed, using the film’s unhurried speed not to tire viewers, but to impress upon them the absolute splendor of Weibo’s settings, the gracefulness of Yianning’s lethal skill, and the humble beats of everyday life. The Assassin was a perfectionist effort seven years in the making for Hsiao-Hsien, and his devotion to detail is obvious in every single moment.