By Brody Armstrong

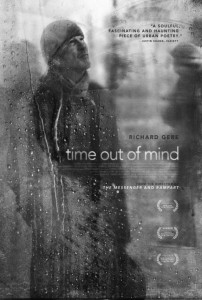

Time Out of Mind, directed and written by Oren Moverman, is an impersonal tour through the daily life of a miserable homeless man named George Hammond. He belongs nowhere, is rejected by his family and wants nothing to do with anyone except for those who loathe him: his daughter and himself.

George is a man on the streets of New York City played by Richard Gere, scraping by, thrifting his jackets in order to buy beer and skipping around homeless shelters. In the opening scene, George is woken up in the bathtub of run-down, abandoned apartment by the manager of the building (Steve Buscemi). The manager kicks him out onto the streets while George pathetically tries to convince him that he’s ‘in between places’ — a phrase he uses when talking to anyone, even his own daughter, insisting that he’s not homeless.

The movie lacks any real exchange of dialogue until it reaches the second half, silently showing the alienation experienced by a homeless man in the city. The shots are raw, yet have an effective beauty about them. Mostly shot through windows or from a fixed angle on a desk or shelf, Moverman gives the viewer a distant voyeuristic perspective of George, akin to what you would see naturally if you were to look out onto the streets of New York City. In shots where he’s walking around the city, people are having conversations — basic ones — that he’s really unable to associate himself with. This produces a powerful effect that emphasizes the feeling of George residing in the city though not belonging to it, a recurring theme.

The movie’s lack of dialogue is filled when he meets another homeless man named Dixon (Ben Vereen) at one of the shelters. Dixon talks George’s ear off as they walk about the city and stay next to each other at a shelter. He embellishes stories and shares mind-blowing facts like one he learned from a doctor (on meth): “Every human male makes enough sperm in two weeks to impregnate every ovulating woman on this planet.” Just like with every interaction with Dixon, George sits stoic and doesn’t respond.

“Would you say something! Anything!” Dixon yells at him after telling him a story of how a man found $60,000 in his shoe.

“Are you the idiot or am I?” George retorts. “I’ve been feeling… that I am just one stupid, fucking loser of an idiot… Am I homeless? I’m homeless,” he says, realizing the disarray his life is in.

Time Out of Mind is as depressing and hopeless as it sounds. It’s made like something that’s attempting to give the viewer an opportunity to be fascinated and learn about this failed human, to observe his life, pitiful and unfortunate. Though what Moverman has done with not having George talk that much until near the end of the movie is clever, building up the viewer’s curiosity for this man.

George admits he’s a “fuck-up,” shows his displacement from the world any time he’s forced to speak, and buys alcohol every time he gets money, making it so the viewer’s curiosity is serviced with reality — or the standard stereotype of an American homeless person, rather. Time Out of Mind is visually interesting, though with its long run-time, lack of an established plot, consistent dialogue and its abrupt and unexplained ending, the movie feels tediously candid.