By Gabriel Sylvester

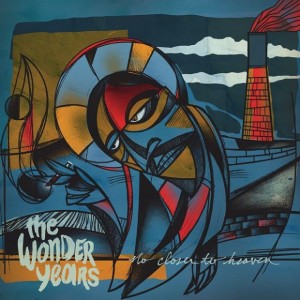

Music, as well as any art, on a very basic level can be divided into two groups: emotional catharsis and entertainment. Music regarded as catharsis can focus on two struggles, internal and external. For bands and musicians that are more focused on the self and on personal struggle, it can be a bit jarring when they shift their focus from the internal to the external through moving from purely personal struggle to depicting how culture and society can shape and influence those struggles. This is what The Wonder Years attempted in its latest album, No Closer to Heaven.

The strongest example of this blend comes in “Stained Glass Ceilings,” in which vocalist Dan “Soupy” Campbell sings of the use of violence and loss of life mixed with his apathetic response, “They were cutting your wings off/ I was staring at my idle hands/ Maybe I could’ve done something.” The song contains obvious overtones of classism and racism, something prevalent in the guest spot by Jason Aalon Butler of Letlive, as he screams, “If everyone’s built the same/ Then how come building’s so fucking hard for you?/ It’s something we’re all born into.” Instrumentally, this song is The Wonder Years at its most unique, incorporating ethereal post-rock guitar lines that build into an aggressive, hardcore-fueled bridge.

The weakest example is in “Cigarettes & Saints,” a heart-wrenching song about the loss of a friend that evokes a lot of emotion, until suddenly toward the end of the song Campbell dedicates the bridge to criticizing drug companies that sell pills to kids to make them feel better. The lyrics come off as clumsy and forced, as if Campbell is suddenly on a pedestal preaching the dangers of drug use. The description of “wolves in their suits and ties” is hackneyed, and his message feels awkward and somewhat insincere. Another example from the album is “I Wanted So Badly To Be Brave” where he talks how abuse leads to violence. This is another important message, but Campbell’s lyrics are again forced and clichéd. “They’re hateful because they’re empty/ We’ve got a chance to break the cycle/ We could be the heroes that we’ve always said we’d be.” This is a statement that’s been used many times, and it feels as if it’s not furthering any conversation regarding the issues he talks about.

Nevertheless, The Wonder Years showcase their growth as musicians, expanding beyond a purely pop-punk sound. No Closer to Heaven is a more dynamic album than previous efforts. It’s a little louder and a little softer, sometimes in the same song. It offers smatterings of post-rock, hardcore, alternative and even hints of folk rock sounds embedded in the unabashedly punk style that The Wonder Years has become known for. One of the highlights of the album, “A Song for Ernest Hemingway,” even opens with a brief a cappella harmony, eventually leading into one of the catchiest choruses this band has ever written, while the final track “No Closer to Heaven” is a calm acoustic reflection, a style the band has not necessarily been inclined toward in the past.

This album is not perfect, but it’s hard to say how deep its flaws go, and how much impact they have on the overall enjoyment of listening. It seems that No Closer to Heaven is a fine experiment from The Wonder Years, one that demonstrates a maturity beyond anything they’ve written both as musicians and storytellers, despite any mixed results in the delivery of their message.