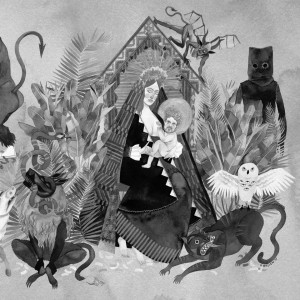

In a way, everything in Father John Misty’s latest album, I Love You, Honeybear, can be summed up in the first and last song. The songs in between make up the filler, the journey from one place to the next; but in the end there is a man, at first apathetic but now satisfied, a simple story that is presented in Father John Misty’s alter-ego Josh Tillman’s trademark sense of wordplay and humor.

In a way, everything in Father John Misty’s latest album, I Love You, Honeybear, can be summed up in the first and last song. The songs in between make up the filler, the journey from one place to the next; but in the end there is a man, at first apathetic but now satisfied, a simple story that is presented in Father John Misty’s alter-ego Josh Tillman’s trademark sense of wordplay and humor.

“Everything is doomed/ And nothing will be spared,” bellows frontman Tillman in the titular track, a sing-songy way of articulating the cynicism that pervades much of Tillman’s work. The song is full of crass imagery: cum-stained sheets, fingering oblivion and admissions of mental illness. However, by the album’s finale “I Went to the Store One Day,” the chaotic and messy nature of the relationships referenced (primarily surrounding Tillman’s wife) has been extracted into something pure, as Tillman sings, “For love to find us of all people/I never thought it’d be so simple.”

I Love You, Honeybear is an album about modern romance. It’s about meeting someone for the first time and falling in love, with all of the vulgar asides and ugly fights that make up a real relationship. Tillman serenades about the difficulty of communication in our modern world (“True Affection”), about being a celebrity and how that affects his lovelife (“The Night Josh Tillman Came To Our Apt.”) and shows the most grotesque sides of himself (“Nothing Good Ever Happens At The Goddamn Thirsty Crow”). He does all of this so he can purge the complicated, cynical feelings he has before the finale, a lovely ballad that tells the story of how Tillman met his wife.

Father John Misty retains its Laurel-Canyon-after-four-beers sound on its follow-up to 2012’s Fear Fun, but it has expanded and diversified as well. The songs run the gamut from Americana, country, R&B and even electronica, but like all great bands, Father John Misty preserves its unique tone. It has developed and widened its scope musically, but it remains fundamentally the same.

I Love You, Honeybear is, beyond anything else, a gift from a husband to his wife. It’s a confession of past sins, an aggressive introspective look at Tillman’s past, present and future. He packs it all up in less than 45 minutes in a haze of inebriated melancholy-drenched rock, culling together disparate relationships and memories into something natural and authentic, something that transcends the trappings of “sad indie rock” and becomes something wholly original. Simple, indeed.