Turning technological limitations into modern art

Born out of necessity, pixel art has gradually changed from a technical limitation to a stylistic choice. Typically, it’s used to evoke nostalgia, but a trend has been slowly emerging over the past decade. Pixel art is finding a home as a sort of modern impressionism: precise enough to convey complicated visuals, but abstract enough to allow the imagination to interpret the details.

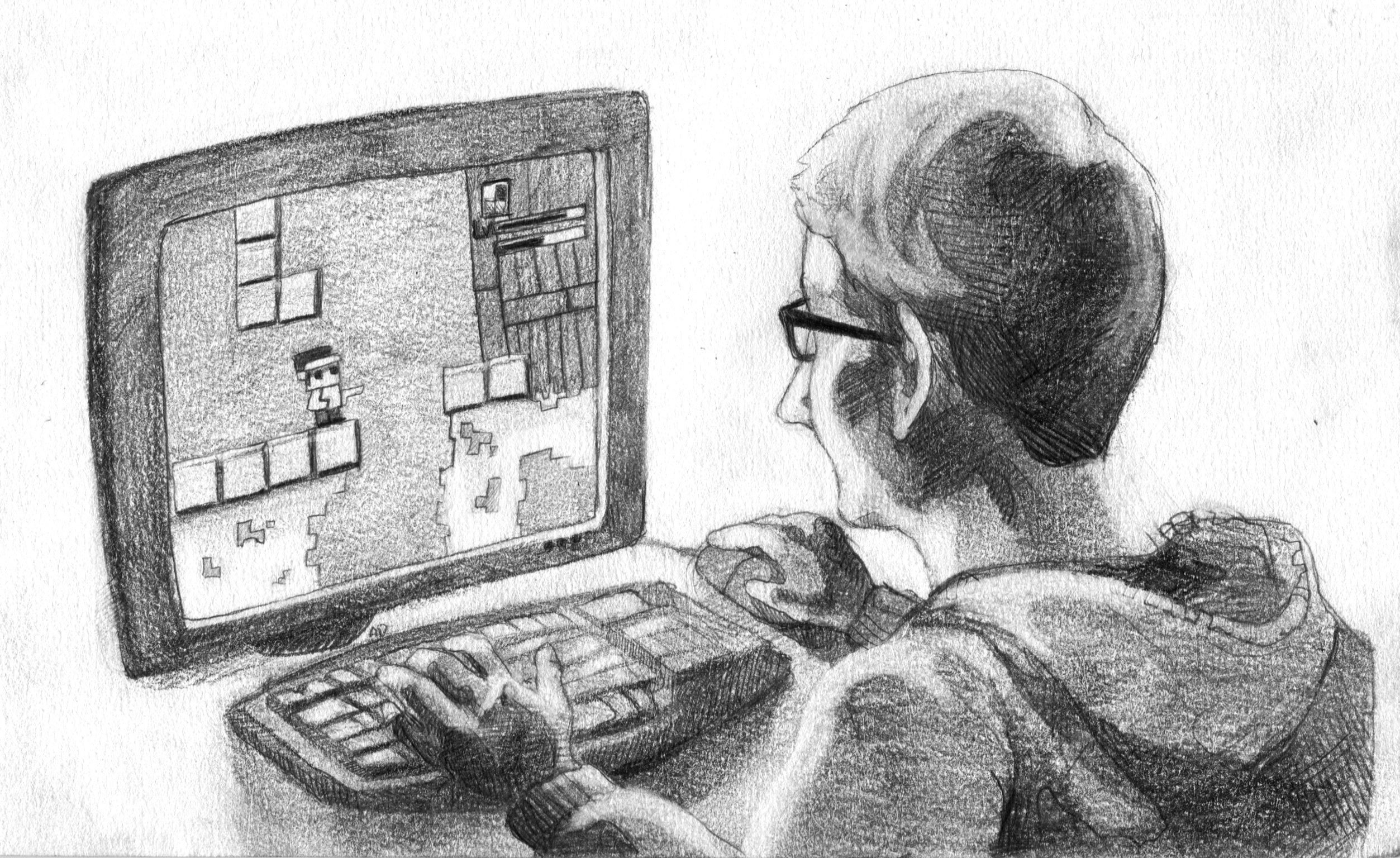

John Roberts, an artist behind noir stealth game Gunpoint, said: “My favorite thing [in pixel art] is its built-in abstract, interpretive nature… It can sound like a cop-out, but your audience gets to read between the lines. In Gunpoint, Conway’s face is only a few pixels across, which lets the player add traits they think suitable; he might be white, Asian or Hispanic, he might be scowling against the rain, he might be scared and frantic as he punches a guard forever or he might be revelling in the bloodshed.”

Gunpoint lets the player choose from a variety of options in conversation, ranging from curt sarcasm to glib banter. By forgoing realism and opting for pixel art, the player can project his or her own idea onto the character, instead of trying to reconcile his or her image with the canon.

Like any style or medium, pixel art has its limitations too. “I also find I can’t play with loose lines too much, or leave shapes undefined, or use messy, interesting brushes,” Roberts said. “I’d suggest that illustrative styles — like those of one of my favourite artists, Ian McQue — couldn’t survive the transition to a clear, defined pixel art style.”

Originally born out of the low-resolution output of early computers and consoles, pixel art is tied to a lack of detail by definition. Miguel Sternberg, pixel artist and co-designer of They Bleed Pixels, said: “When you’re thinking about a design, you’re thinking about what’s going to work well at that very small scale and have some uniqueness to it. After you get down to a certain size, you get only so many permutations.”

Without using cartoonish proportions, smaller-sized characters are forced to use more overt traits and attributes to leave their mark on the viewer.

“The fact that there are these holes that need to be filled in by the player’s mind is a strength, the same way that sometimes writing about a scene, instead of showing a picture, and allowing the imagination to fill in the details — that can be a strength as well as a weakness,” Sternberg said. Pixel art’s ambiguity is a positive trait if it’s used deliberately.

Ignoring minute details allows for extra attention to other areas. “It’s also fantastic as a tool for improving your art in general,” Roberts said. “Often it’s easy to get hung up on rendering and shading, but since most pixel art barely allows more than a shadow and highlight, it makes you concentrate on better form, pose and composition.”

Games like Cave Story trade graphical fidelity for refined, fluid animation to great effect. Vibrant environments and characters are deeply expressive and bouncing with life.

“Most people are working in a size where there’s a huge range of possible things you can represent, even if you can’t show the earrings on a character, or a cool belt buckle,” Steinberg said. “There’s still a lot of unique stuff you can do with the shape of character, costume, etc.”

As pixel art moves beyond its origins in technological limitation, it’s pushing to spread beyond gaming.

“It also depends how you define pixel art,” Roberts said. “I’m going to be an art wank for a second and suggest that pixel art is just constructing large designs from small, regular components. Then I can say that Van Gogh was a pixel artist or Lego builders are pixel artists. Both use shapes to suggest unseen detail in an abstracted piece and allow the viewer to interpret them differently.”

“So, basically, I’m just like Van Gogh.”

Will Uhl is a sophomore journalism major who likens the art of E.T. for Atari 2600 to Starry Night Over the Rhone. Email him at wuhl1@ithaca.edu.