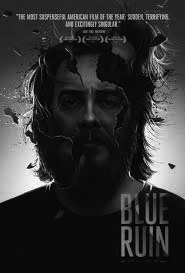

Blue Ruin is a not-so-typical revenge thriller with a satisfying art-house twist. The first 20 minutes of the film are bathed in an inclusive suspense, all completely devoid of any dialogue; the audience is introduced to a frail looking beach bum, Dwight, who viewers familiarize themselves with simply by watching him live. By day he scavenges suburban areas for food and other necessities, and by night he returns to his home — a derelict Pontiac in the middle of a secluded field. One gets the sense that this is his only possession from a former life. It is undoubtedly the item responsible for the film’s title: a “blue ruin” of sorts. Shortly thereafter he discovers that the individual responsible for the murder of his parents has been released from prison, and so his quest for retribution is set ablaze.

Jeremy Saulnier plays both the roles of director and cinematographer for Blue Ruin, which is his second feature film. Funded mostly by Kickstarter, Blue Ruin is particularly impressive for being shot on such a modest budget — moreover, it is a piece of cinema that is truly impressive on nearly all fronts. As cinematographer, Saulnier brings his vision stunningly to life; color palettes change as the film progresses from blue nostalgic undertones at the beginning, to warmer shades indicative of the impending wrath at the climax.

Macon Blair plays the lead role as Dwight, and does an impeccable job portraying a man who doesn’t seem to be quite cut out for the all-American revenge game he’s thrown him-

self into. From behind his bushy beard, there is fear in his eyes; Dwight seems to think that revenge is the only solution, but is it truly what he wants?

The film plays with the audience’s expectations in these ways. This isn’t the Charles Bronson revenge film we’ve familiarized ourselves with, where the hero mows down groups of bad guys after falling victim to an act of unthinkable brutality. No, Blue Ruin isn’t interested in satiating our tastes for those romanticized visions of bloodshed that have become so popular in modern films. Saulnier seems interested only in exploring the consequences of violence, and the unfortunate circumstances that give rise to it. As Dwight silently contemplates the morality of the situation unfolding around him, one is exposed to the tragedy of victimhood. By the end of the film, everything feels bathed in blood. It’s an unsettling but sobering experience.

The film’s implications become particularly evident in a scene where Dwight watches a bullet pass through someone’s head, and we hear the shooter murmur, “That’s what bullets do.” The question arises, why has Dwight chosen this route? Saulnier seems to be analyzing the place of guns in our culture. He asks us to question the morality of a society that romanticizes firearms and, in certain regions, clings to ideological beliefs reminiscent of Sergio Leone’s representations of the Wild West. Living in a world saturated with hammers, does every problem start to look like a nail?