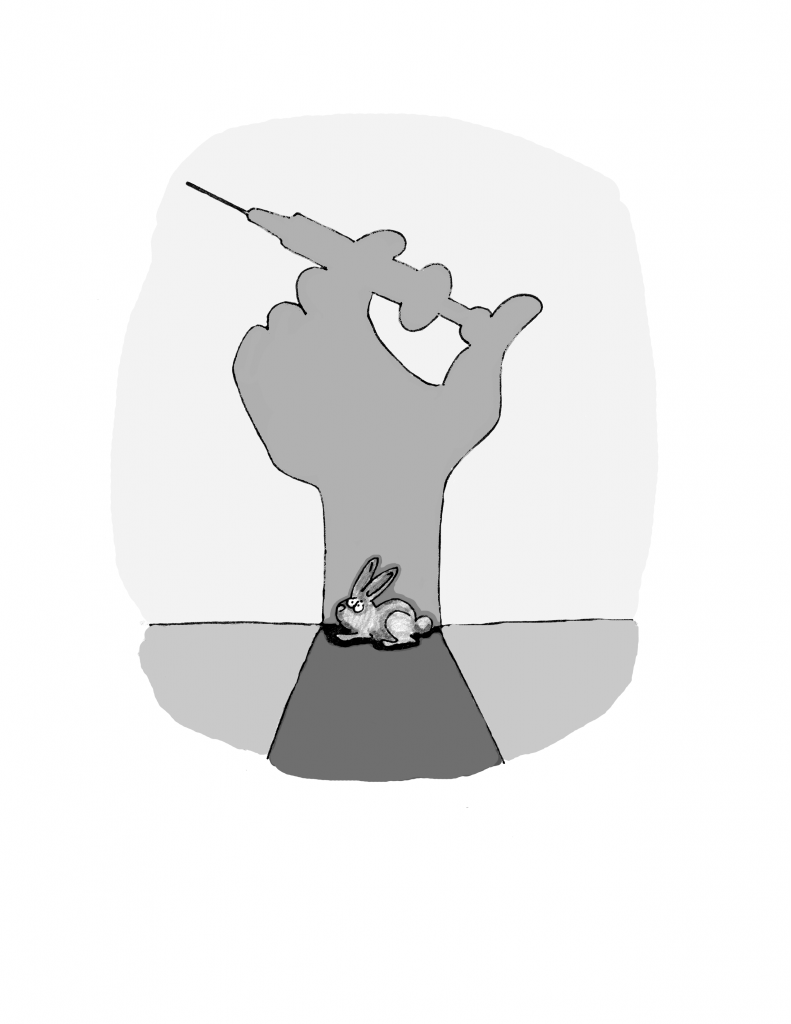

Image by Lizzy Cox

Every day, hundreds of thousands of animals that we usually don’t keep for pets are caged and grossly mistreated by food and medical industries internationally. As of 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated there were roughly 20,000 factory-farms on location in the US. This, of course, does not take into account the past five years of increases, which in many cases is a more shocking statistic. The number of U.S. cows on factory-farm dairies, for instance, have nearly doubled to 4.9 million between 1997 and 2007.

Conditions for many of these meat packing and dairy industries are often compared to those faced by inmates in federal prisons, both of which are the result of poor regulations and overcrowding. Whereas prisons are typically thought to have their inmates come to them, however, factory-farms are actually breeding entire populations of animals at their sites in order to sustain the high demand for meat in America.

“I think it’s like the holocaust, to be honest,” Ithaca College student Olivia Stroud said. “It’s a crime, and actually the reason why I don’t eat meat at all.”

Some people see organic farming as an alternative to the mistreatment associated with factory farming. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, “Organic food is produced using sustainable agricultural production practices. Not permitted are most conventional pesticides; fertilizers made with synthetic ingredients, or sewage sludge; bioengineering; or ionizing radiation.” As for live animal upkeep, the requirements are a bit more vague, stating that organic livestock must be “Allowed year-round access to the outdoors except under specific conditions (e.g., inclement weather),” which includes “shade, clean and dry bedding, shelter space for exercise, fresh air, clean drinking water and direct sunlight.”

Jerry Dell Farm is a roughly 1,000 acre dairy farm located in Freeville that has been operated since 1946 but became certified Organic in 2000, distributing to companies in New York and the neighboring states. Due to non-profit organizations like Cornucopia Institute in Wisconsin, which regulates organic farming practices and works to educate the farming community, organic dairy farming is mostly the same throughout the US: free of chemicals, pesticides and hormones for both the cows and the field.

Jeremy Sherman, who has been operating the farm since 1976, said he has nothing against conventional means of farming, but that he felt that organic farming just suited his agricultural preferences.

“I just didn’t like the conventional style of total confinement,” Sherman said. “I like cows outside eating grass … I didn’t really like the direction I was headed in with [conventional] farming, so I went back to the way I grew up.”

Other groups, like Peta, argue that the term USDA organic says nothing about the welfare of the animals, that it is just a label used to disguise what is essentially still a cruel practice. Kenneth Montville, Peta’s College Campaign Coordinator, said that their organization makes no distinction between organic and inorganic.

“Terms like organic, inorganic, free-range and cage-free really have little to no meaning when it comes to the industry,” Montville said. “These are cooked up terms that are meant to appeal to people that care about the treatment of animals. If 10,000 chickens are kept in a dark filthy shed, but they’re kept in a giant kennel rather than individual cages, those chickens are ‘cage-free.’”

Regardless of whether or not organic animal products are a significant alternative, recent awareness of the past few decades of farm animal abuse in general have led some people to take protest. As the largest animal rights activist group in the country, Peta is often criticized for their extreme punishment of food companies as well as consumers. In fact, some people say they are turned off from the issue of animal cruelty altogether due to the methods like abrasive means of advertising taken by Peta and other more extreme groups.

Some organizations take a completely different tactic in fighting for their cause of humane animal treatment, favoring helping farm animals directly. Couple Jenny brown and Doug Abel, the founders and staff of Woodstock Farm Animal Sanctuary in 2004, work with their staff on and off the farm to give better conditions to farm animals who came from factory-farms. The organization provides a home for abused, neglected and abandoned farmed animals that have removed from various locations. They also conduct educational tours, giving visitors a chance to meet the animal-residents and learn about the group’s cause.

Susan Foster, programs Director for WFAS, said that We believe that all animals, including farmed animals who are the most abused and least protected in the world, deserve to live a life free from fear and suffering and able to just be the sensitive, unique individuals they are.

“We believe that all animals, including farmed animals who are the most abused and least protected in the world, deserve to live a life free from fear and suffering and able to just be the sensitive, unique individuals they are,” Foster said. “We have no need for meat, dairy or eggs and, in fact, it is very unhealthy for us and for our planet. So we also teach people about the many benefits of a plant-based diet.”

While factory-farms are the largest factor in worldwide mistreatment of animals, the issue of animal abuse extends beyond the food industry and into animal testing for research purposes. This practice has existed as far back as 310 BCE, with the anatomical studies of Aristotle and Erasistratus, but is now conducted mainly for research on diseases and bacteria amongst a multitude of sciences.

Today, many are skeptical about the ethics of animal treatment, wondering whether or not the benefits are even worth the efforts. Even within the scientific community the debate exists. Dr.Elias Zerhouni, former director of the National Institutes of Health said that animal testing is an outdated idea.

“We have moved away from studying human disease in humans,” Dr. Elias Zerhouni, former Director of the National Institutes of Health said. “We all drank the kool-aid on that one, me included. The problem is that it hasn’t worked, and we can’t keep dancing around the problem … we need to focus and adapt new methodologies for use in humans to understand disease biology in humans.”

Cornell University Center for Animal Resources and Education is a veterinary service offered by the school that also advises and educates researchers on careful animal testing. According to the center’s online mission statement, “The mission of CARE is to ensure quality animal care and welfare while serving the Cornell research and teaching community through education and collaboration.”

Still, many other scientists argue that animal testing still plays a crucial role in scientific discoveries. After all, 75 out of 98 Nobel Prizes awarded for Physiology or Medicine were directly dependent on Animal Research. Dr. Mary Martin, chief of veterinary and educational services at Cornell University, said that contrary to popular belief, most researchers conducting tests on animals work to keep their practices as humane and comfortable for the subjects as possible.

“Before research can be conducted in animals, researchers proposing the use of animals must do database searches to look for alternatives to the use of animals, or ways to minimize or eliminate any pain or distress,” Martin said. “Research is highly regulated by the USDA and Public Health Service to ensure animal welfare.”

Despite efforts to humanize the use of animals from farm to factory and from vendor to laboratory, the discussion still continues about treatment towards these living creatures. who cannot verbally communicate their level of pain and discomfort to us. Whether the decision is made to punish animals, human action, or consumers who turn a blind eye, the true solution may lie in education on the matter. For those who see or participate in the cycle of cruelty and punishment, the goal should be in halting the cycle with open-mindedness instead.

____________________________________

Tylor Colby is a freshman writing major who is staying far away from Old McDonald’s farm. Email him at tcolby1[at]ithaca.edu