Image by Jessica Bruehert

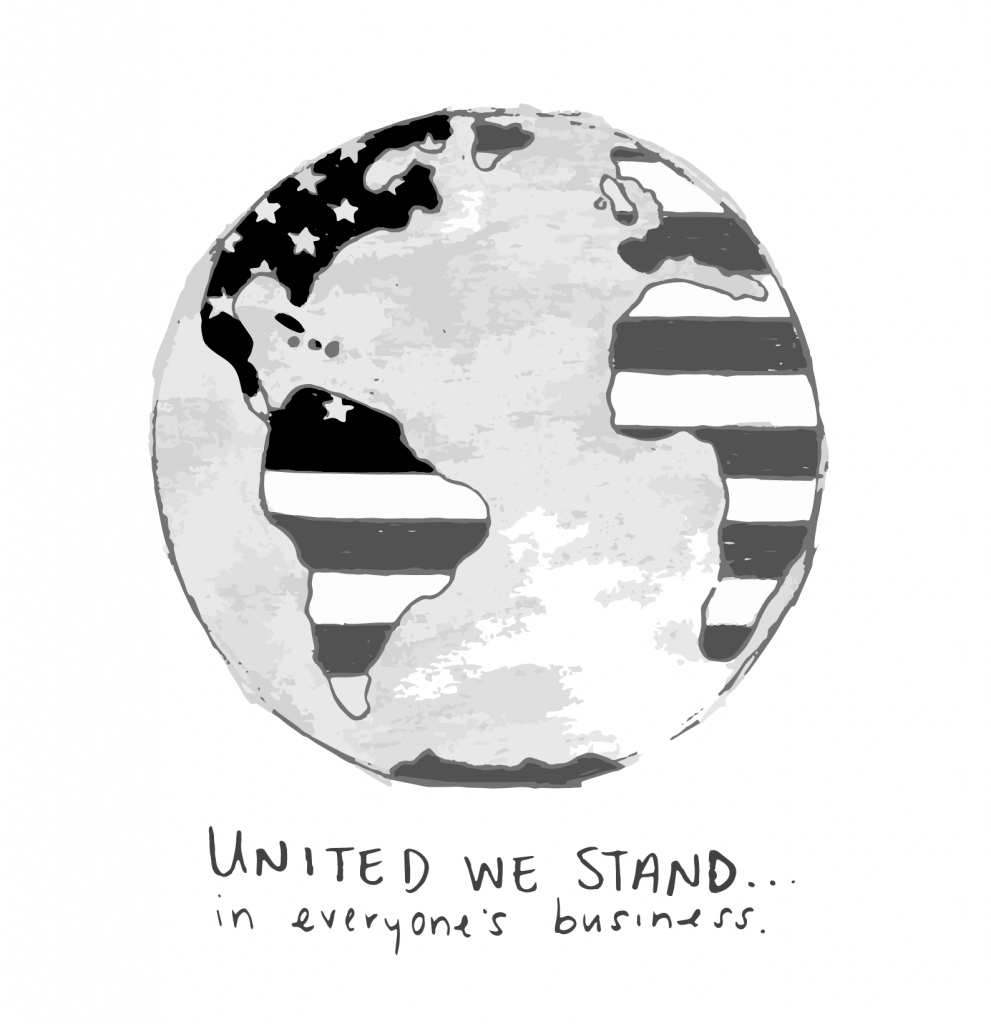

The United States unofficial role of global police

At 2:45 p.m. on August 21, reports of the use of chemical weapons came flooding in from towns near Syria’s capital city of Damascus. Within hours, videos and graphic images were flooding the internet. Piles of bodies including dead woman, children and babies lined the streets with no signs of external damage. All evidence led to the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian dictator Bashar Al-Assad.

The US has yet to take any definitive action in response to this clear violation of human rights which once again brings up the question of the US’s role in the international sphere. Should America be acting as global policemen? And what even qualifies the US for the job?

Though the US is considered to be the leading world power (Obama is still top 5 on Forbes’ List of the Worlds Most Powerful People 2013), the US could be falling fast if it continues on this intervention path.

America stands strong (and arguably alone) in this position. Leaving the international community with the question: How can America condemn other countries when they have left a trail of reprehensible activities (unjustified invasions, backing of oppressive regimes, being a supplier of WMDs) all across the globe?

In order to fully examine the origin of this title, it is critical to analyze US history. Post-World War II the leading powers on the global stage began to shift. Great Britain, Germany and France were all economically devastated, which then allowed America and the Soviet Union to step to the front of the stage. In 1989 when the Soviet Union collapsed, America became the de-facto global superpower and has retained the title ever since.

Ranking No.1 on the Business Insider’s “Ten Most Powerful Militaries in the World,” it is not surprising that other countries look to America in times of crisis. Intervention involves a solid and heavy military backing. According to the Peter G. Peterson Foundation the US’s military budget equals out to more than the other top 10 military budgets combined, allowing for a larger budget for military intervention.

But the question of what criteria motivate the US to intervene still remains a largely unanswered question.

According to Lisa Sansoucy, Ithaca College politics professor, US interventions are largely dependent on one criterion. “I think it depends on how the U.S. defines its national interest,” said Sansoucy “whether in material (military, economic) or ideational (democracy promotion, human rights) terms.”

Sansoucy pointed out examples of materially driven interventions such as Panama in 1989 and Guatemala in 1954, as well as more normative-driven instances such as Vietnam (1960-1975) and Somalia (1994).

However, Sansoucy was just as perplexed by the logic behind non-interventions as many other critics are of the US’s global policeman role.

“It’s also important to consider non-interventions” said Sansoucy. “For example, why did the U.S. choose not to intervene in China in 1949, Chile in 1971, and Rwanda in 1994?”

Perhaps there will never be solid answers to these questions, but a pattern seems to be emerging between US interests and their interventions.

Peyi Soyinka- Airewele, IC professor and president of The Association of Third World Studies (ATWS) proposed perhaps a more important question about the interventionist role of the US.

“Should the US be involved in any kind of unilateral intervention at all- irrespective of whether it is in Libya, Egypt or the Congo,” questioned Soyinka, “or do we need to be having wider conversations about creating a more ethical and legal framework of multilateral interventions?”

Since the discussion of intervention in Syria, numerous editorial writers in new outlets such as Reuters, The Courier Journal, New America and Foreign Policy have suggested that perhaps the US should back off its unilateral interventionist tendency and address domestic issues before attempting to hand out band-aids to the rest of the world.

Perhaps it is merely a matter of opinion. Barbara Conry, a former foreign policy analyst at the Cato Institute, examined in her policy analysis US Global Leadership: A Euphemism for Global Policemen the idea that the US’s illusion of being so-called global policeman could be a slippery slope.

“Global political and military leadership is inadequate, even dangerous, as a basis for policy,” Conry wrote. “The vagueness of “leadership” allows policymakers to rationalize dramatically different initiatives and makes defining policy difficult. Taken to an extreme, global leadership implies U.S. interest in and responsibility for virtually anything, anywhere.”

Perhaps America should take a look in the mirror before they continue their global crusade for democracy and equality. A country that is still fighting for equality for all and maintains a preposterous inequality of wealth trying to police the world seems to be a little ironic. Maybe the US should switch its focus, move its line of vision from encompassing the whole word and hone in on its issues at home.

____________________________________

Sabrina Dorronsoro is a junior journalism major who will be dressing up as a global superpower next year for Halloween. Email her at sdorron1[at]ithaca.edu.