The wind tugged at my hair as I swished through the air on the Cloud Swing, a high-flying circus act. I pushed my toes upwards, visualizing kicking straight through the roof of the big top. Pumping on Cloud Swing is similar to standing on a playground swing, only 50 feet off the ground and I wore a safety belt. I slipped my feet into a secure wrap and at the peak of the swing, released my hands from the ropes and leaped. With arms outstretched I dropped forward into the open air.

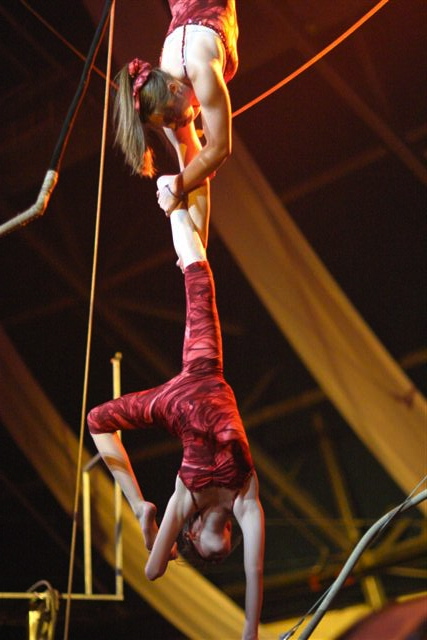

After a moment of weightlessness, I felt the tight jerk as the wrap caught my feet and I rode the swing one more time, suspended upside down. People in the audience may think the leap was the hardest part of the trick, but climbing back up is the real challenge. I spent hours conditioning and training my body to fight the pull of gravity and inch back up to standing position in a hopefully graceful manner. By the time I returned to the reassuring firmness of solid ground, my arms were shaky from exhaustion.

This is a typical practice session I experienced during 12 years as a member of a youth circus. I started as a 7-year-old performing on trapeze and did not leave until I turned 18 and moved away to college. Being in the circus made for an odd childhood. I can’t spiral a football correctly and remain baffled by the rules of Ultimate Frisbee, but I can jump rope while walking on a ball, ride a unicycle, and complete a pass on the flying trapeze from the swinging bar to the catcher’s arms. While my classmates strapped on soccer cleats after school, I changed into a leotard, and as they headed onto the turf, I strapped on a safety belt and climbed into the rafters of the big top.

Circus Juventas is a non-profit performing arts school in my hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota. When Circus Juventas first opened in 1994, it was a small collection of local kids that met in the gymnasium of the local rec center. In 2001 they expanded to a custom-built, permanent big top tent. It is a non-profit community organization that provides after school programming for youth in the area.

Training takes place throughout the afternoon and evening with performances staged a few times a year. There are over 800 students between the ages of three and 21 banking on the chance to run away to join the circus but be home for dinner. Coaches come from all over the world and have often worked with first-class companies such as Cirque du Soleil and Ringling Brothers. Most participants take classes recreationally as I did, but a few advanced students do attempt pursuing circus professionally. The acts offered include wall trampoline, teeterboard, contortion, triple trapeze, unicycle, acrobatics, hoops, silks and flying trapeze.

As a modern performing arts company, Circus Juventas is very different from a pop-up sideshow. We have choreographed routines, large audiences and sparkly costumes, but there are no animals, no traveling and we go to school like everyone else. “In the 1980s there was a renaissance if you will, of a more intimate style of performance,” Janet Davis, author of The Circus Age: Culture and Society under the American Big Top and chair of American Studies UT Austin, said. The Canadian company, Cirque du Soleil, emphasized the theatrical side of circus and aimed to honor the spectacle of constant activity while showcasing individual artists. In this current trend, a narrative loosely joins the whole show that targets adult audiences and animal acts play a smaller role, if any role at all.

American circus performers have found this a tough market to enter. “Circus arts in America are more stigmatized in a way they are not in European countries or Asia and some Latin American countries too … There have been some American stars but the majority come from elsewhere and even the Americans are usually descended from a long line of performers of European origin,” Davis said. In addition, the circus is usually a family business, an institution you are born and raised in so that performers may be the tenth generation working an act. The U.S. is so young that American artists simply do not have that legacy.

As of yet, nothing can compare to the elite, state-sponsored circus training school in Montreal, but the U.S. is gradually building a reputation of its own. Youth circus schools are increasing in popularity and have popped up in many American cities from Circus Harmony in St. Louis to Circus Smirkus in Greensboro, Vt. The American Youth Circus Organization counts more than 270 members across the country. Several of my coaches came from the Sailor Circus school in Sarasota, Fla., which is the oldest circus school in the US, according to their website. It is nicknamed the Greatest “Little” Show on Earth. Illinois and Florida State Universities even offer the option of circus training paired with college curriculum.

For much of my youth, I felt more comfortable upside down than right side up and am completely at home perched on the thin bar of a trapeze. For shows, I performed choreographed routines while dressed in a tight costume and nearly blinded by spotlights. The adrenaline of performing is fun, but I much preferred the hours of practice sessions. I liked having no audience and just focusing on the coach’s directions in order to work towards the next harder trick in my act.

I basically grew up in the circus, since I started at such a young age. I knew some coaches from childhood and became incredibly close with teammates. I put my life in the hands of these friends and spent hours huddled with them backstage anticipating our turn on stage, not to mention collapsing in a heap while attempting a human pyramid or spotting each other on a trapeze. My two older sisters were also in the circus so it became a family affair, just as circus ought to be. To my mother’s dismay we constantly practiced in the living room — endangering nearby picture frames and china plates — and experimented on the monkey bars in the backyard.

As performers, circus kids are inclined to be dramatic, and there was always a good amount of gossip. The environment creates tension and competition as students vie for spots on an upper-level performing team, though the circus was without a formalized structure for advancement. As a younger performer you idolize the older kids. It was incredibly rewarding when I started coaching beginner’s classes and passed on my knowledge to younger students.

I am primarily an aerialist, which means I trained in acts where the performer is suspended in the air. I am a pretty terrible acrobat, so I can’t pull a spontaneous back tuck as a party trick and generally require equipment to perform. Besides “Cloud Swing,” I focused on an act called “Spanish Web,” a rope you climb and tie a hand or foot into while someone below spins it in a circle. The force of the circular motion brings your body up horizontally midair. If the spinner was very fast, the skin on my face would smush forwards and my toes would go numb. On the floor, I worked on German Wheel where the performer stands inside a round, metal frame and rolls rapidly across the stage. It is an unmatchable feeling to complete an entire routine in these acts, executing every trick with perfect form and timing. Resigning myself to working out at a gym is not particularly appealing in comparison, though at least no one will tell me to style and smile when I step off the elliptical.

By the time I graduated from circus, I felt ready to move on and had grown tired of some of the drama and internal politics over who got to perform in which act and when. It had become just another thing I did along with Habitat for Humanity and Hebrew School. I realize now that I only partially recognized how special it was. I get flashbacks to the weightless feeling of leaping from the “Cloud Swing” and realize I will never again be so close to flying.

____________________________________

Moriah Petty is a junior TV-R major who can never hang up her leotard for good. Email her at mpetty1[at]ithaca[dot]edu.