Does objectivity exist in modern day media conglomerates?

Image by Karen Rich

In the modern age media permeates every aspect of people’s daily lives: delivering instructions on what to wear, how to think, what is important and what is not — and everything in between. As is often the case, however, in the mad dash of progress toward a centralized, business-driven and essentially corporatized media network, some things have gotten lost in the shuffle. This seems to include journalistic integrity and legitimate investigational reporting.

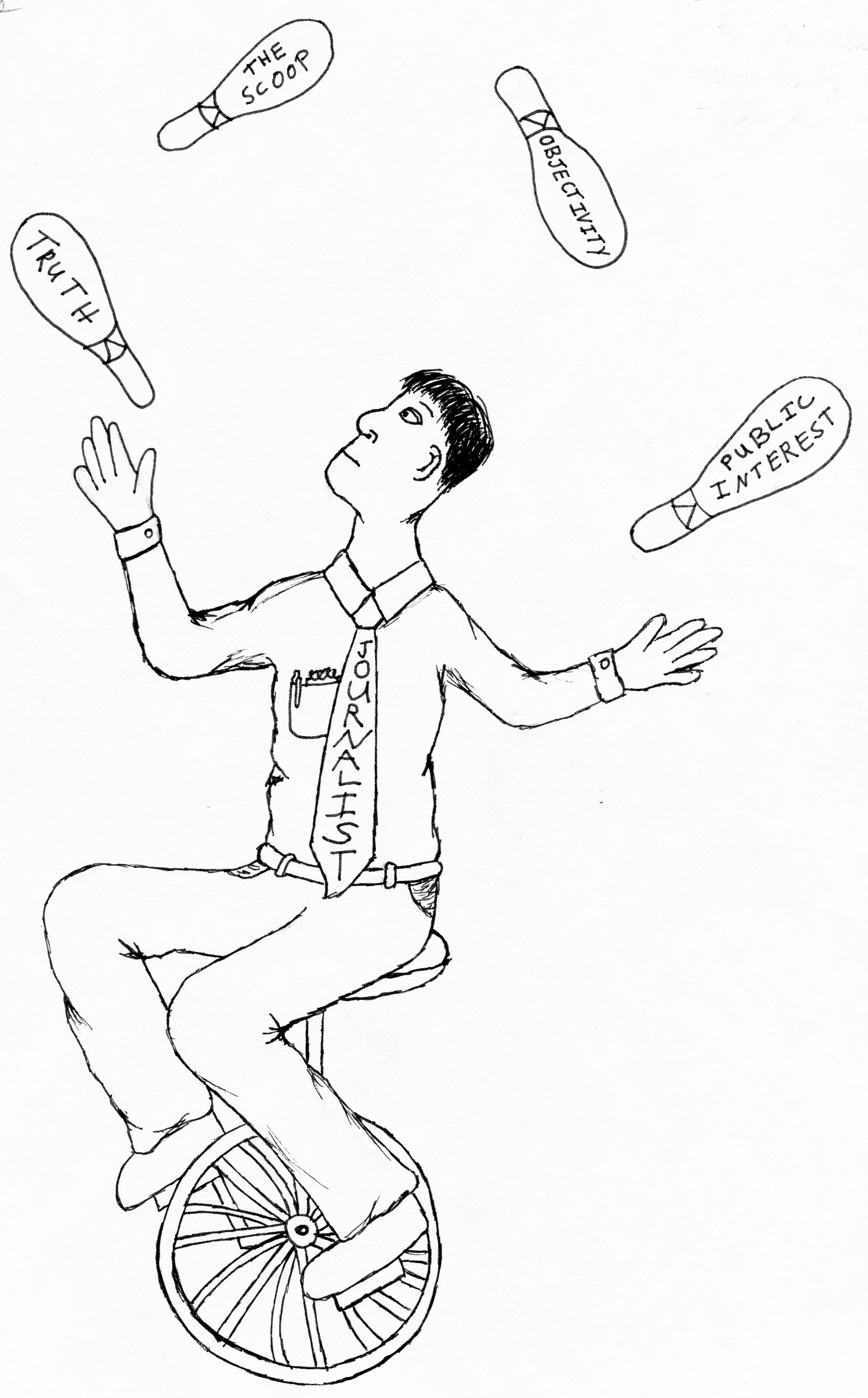

The popularized term “media circus” describes the current situation rather accurately. The corporate media show features players at all levels. There are ringmasters; the anchors and reporters more concerned with looking glamorous and getting the scoop first. There are lion-tamers; pundits on both sides of the political divide more interested in shouting over each other on national TV than actually having a reasonable discussion about the issues at hand. Finally, there is a high-wire act; the false cliffs of black-and-white, oversimplified dilemmas as portrayed on cable news and the list goes on.

One foundational tenet of journalism, though not included in the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics, is “objectivity” — analysis based on observable phenomena and facts, uninfluenced by emotions or personal opinion. The more corporatized the media becomes, however, the more closely it becomes associated with the very power it is supposed to monitor. This creates a conflict of interest that prevents media groups from digging too deeply into issues that might be harmful to their advertisers or parent corporation.

Robert Jensen, a writer and professor of journalism at the University of Texas at Austin’s College of Communications, said he does not take objectivity very seriously, and would prefer that reporters simply tried to be honest with the public.

“In the traditional sense, objectivity is just a cover for an overwhelming identification with the status quo and people in power,” Jensen said. “All media and all people are ideological, so rather than pretending to be outside that journalists should really focus more on how those ideologies affect what people do.”

Jensen also said that the problem of bias and sensationalism in the media is actually centered on an overarching economic situation.

“At the core of all this debate is a question about capitalism, and whether it is consistent with building a decent human community,” Jensen said. “As long as we are stuck with a capitalist economy and a corporate monoculture, a media that is rooted almost entirely within that for-profit model is going to be inadequate to produce the kind of journalism our society needs.”

In the future, Jensen said he would like to see more public-funded television and radio outlets like PBS and NPR, along with support for alternative media and citizen journalism.

A report published by the organization Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) this February cited numerous recent instances of corporate values intruding on the newsroom.

Last September, for example, the Washington Post published a two-page spread devoted to a debate on U.S. energy policy that featured many supporters of oil and gas drilling, but no critical voices; this might have been because the debate was sponsored by subsidiaries of the American Petroleum Institute. Normally papers are expected to accompany articles with a disclaimer if a conflict of interest could arise, but the Post published no such warning.

Additionally, a journalist at Motor Trend magazine was revealed last November to have accepted money on the side from oil company Phillips 66; this is a violation of most codes of journalistic ethics, as being both a writer for a supposedly impartial publication and a paid spokesperson for a company is a clear conflict of interest. When questioned on her actions, the journalist saw nothing wrong with what she had done, adding that any other reasonable person living in a capitalist society would also expect to be financially compensated for work.

While corporatization can be a factor in the degradation of media coverage, Steve Rendall, an analyst for FAIR, said that conglomeration is not a new development and is inevitable for most news organizations.

“The idea that there was ever a ‘golden age’ of media is a popular misconception,” Rendall said. “News is and has always been a corporate effort no matter what, even if it’s a small mom-and-pop operation. As long as these groups rely on ads for revenue, they will in some way be beholden to business interests.”

Rendall said that journalists should not always be blamed for poor content, as most decisions in the media today are made by corporate CEOs who have little to nothing to do with newsgathering.

“When you get further and further away from the ideals of journalism and companies start to be run by MBAs, everything becomes a position about money,” he said. “When businessmen start making decisions what you get is downsizing, cutbacks and closing of foreign offices, and that leads to a lower quality of information.”

Rendall also said corporate media comes with a built-in conflict of interest.

“If you’re a publically traded company, you are bound by law to protect your stockholders’ assets,” he said. “Many stories that a journalist may think are in the public interest are actually against their parent company’s financial interests, so the decision on whether or not to publish becomes a lot more complicated.”

According to an infographic compiled by the website Business Insider, six large companies currently own over 90 percent of media outlets in the U.S.; in 1983, only 30 years ago, there were nearly 50 companies competing for dominance in the field.

One of the most well-known of these conglomerates is News Corp, owned by billionaire media tycoon Rupert Murdoch. The company’s properties, including Fox News, the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, are prone to reflecting the conservative political leanings of its owner.

Other companies on the list include General Electric, which owns the media empire of (the majority of) NBC; Time Warner, owner of CNN; and Disney, whose properties include ESPN and ABC. Especially in the case of GE, a company known for producing widely used commercial products and with a record of environmental violations, the possibility of a conflict of interest arising and reporters being pitted against their parent company on a matter of principle greatly increases.

Jack Shafer, a media critic and opinion writer for Reuters, said that in his years as a journalist he has seen many examples of sensationalism and press irresponsibility, particularly regarding the topic of the government’s war on drugs. He said the media today has developed a bad habit of taking what authority figures, such as police and federal prosecutors, say at face value. While this can be due to laziness and innocence, it sometimes has a more societal motive.

“It’s difficult for journalists, or anyone for that matter, to go against the current,” Shafer said. “When you have an almost century-long drug war with massive amounts of propaganda being produced about the government that spreads lies about drugs to the public, it becomes very hard for individual journalists to push back and challenge those ideas.”

Shafer also said journalists are often hesitant to revisit stories they consider old and tired, and that may not attract a large enough audience to have relevance. He said he was hopeful, however, that change might be on the horizon for the drug issue.

“There are some notions that have become so fused to the cultural body that it’s difficult to separate them,” Shafer said. “But as marijuana approaches quasi-legal status in this country, I think a lot of people will start realizing that what they were told about the dangers and horrors of drugs are not true, and that in turn may lead them to question other things as well.”

At its core, it seems that contemporary commercial media in this country is tied to the notions and philosophies of American capitalism. While many smaller and more independent outlets are emerging to take on the duty of presenting truth to the public, this corporate power paradox leaves mainstream media with a debilitating ethical dilemma that will not be easy to resolve.

____________________________________

Kyle Robertson is a junior journalism major who is certain that General Electric does in fact own everything. Email him at krobert4[at]ithaca[dot]edu.