Image by Karen Rich

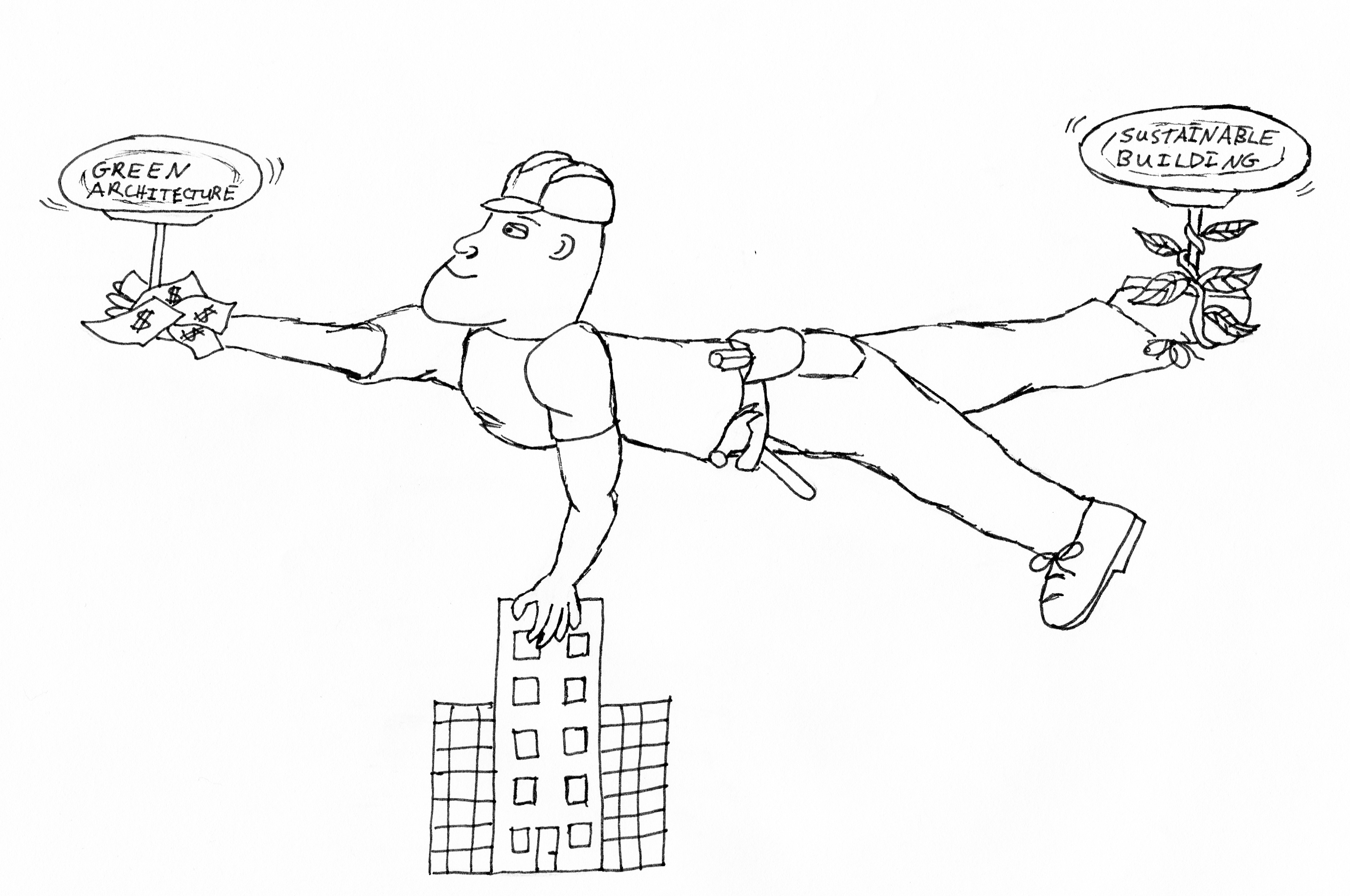

Finding a sustainable balance for architecture of the future

Sustainability is the goal of today. Achieving it, means addressing it in all parts of our lives: our everyday behaviors, how much materials we demand, how many things we have and how we make those things from.

We need to begin to redesign various systems, moving them away from carbon intensive processes while preparing for impending consequences of climate change. According to Architecture 2030, buildings in the U.S. account for 46.7 percent of emissions.

When people think green building it is LEED, an acronym for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, immediately comes to mind. LEED is a certification system developed by the non-profit corporation, the U.S. Green Building Council. The program offers several standards based on the type of building project and depending on how many standards a project can meet the USGBC awards the certification of LEED Gold, Silver and Platinum. The goal of LEED and of the USGBC is to provide incentives for people working at different scales from residential to large scale commercial to plan for sustainability form the drawing board. Over 10,000 certified buildings later the program is even influencing policy. In Washington D.C. for example, all public buildings must now be LEED certified. The success of LEED has even led to the development of SEED, an urban planning counterpart that provides tactics and standards for planners and developers to strive for on a sustainable urban development scale.

However, LEED is contending with many criticisms. Many architects argue that LEED has become more about attaining acclaim than about attaining sustainability. Architects also argue that LEED only offers a very rigid path to certification, which is often expensive and technology intensive. Many believe the conversation in architecture should be more intensive and holistic, looking at how buildings can work more intuitively with nature. LEED has cornered the market on green building, positioning it as almost the only way to go green in building. As of now, once a building achieves LEED it’s certified for life; there are no protocols for backup checks, making sure these buildings are actually saving energy and no way to take back awards if buildings aren’t performing up to par.

Mark Darling, Ithaca College’s sustainability programs coordinator, pointed out major positives and unintended negatives regarding LEED. According to Darling, LEED provides streamline standards that are ingratiated into the existing building code, however, getting certified is expensive. A phenomenon that has developed as a response is buildings being designed to LEED standards but not going for certification that adds additional costs to the project. “That’s a justification a lot of people are using” Darling said. “But how do you support the program? That’s how USGBC gets the money to do research and development. It’s a matter of community as far as I’m concerned. This is about sharing; if you pay for your building that means this [LEED] can continue to go, if you value that then you should pay for the value.”

The next major issue is educating occupants of the project on how to work with the building technology to ensure maximum performance. According to Darling, in one of the LEED buildings on campus there were specific outlets designed into the building where you were supposed to put computers, because they were separately monitored. People then came into that space and plugged other things into those outlets. “There’s been this whole learning curve of learning how to adjust the systems and make people understand how to work with the system.”

Architecture is naturally a discipline that often takes part in introspective analysis of its purpose and praxis, but economic downturn and recent increased frequency of major weather events have brought climate change to the forefront of public discourse, causing architects to rethink what it means to design with the environment in mind. Symposiums like “Sustaining Sustainability” that took place at Cornell University last year, are becoming all the more necessary considering that the fundamental purpose of architecture is separating humans from the environment or from “extremes” and that must now be rethought. Sustaining Sustainability re-envisioned the “home” as zone for interaction between humans, plant and animal life, and experimental bio materials that would allow a building to react to changes in climate like a living organism.

As needed as these imaginings of new sustainabilities are, the world needs buildings now and we can’t wait for theory. We need accessible replicable codes that can be applied to the renovation of existing buildings and instituted in new buildings now. Streamlined systems like LEED provide this and make great starting points

The final frontier will be negotiating green design systems with the behaviors of people on a daily basis which is always a variable. This is the last and most essential key: we need to not only normalize sustainability but also design to ensure sustainable decision-making. If we can’t engage in the social and monitor our personal responsibility than nothing will change.

____________________________________

Andreas Jonathon is a junior architectural studies major who knew he wanted to get into green architecture when he only built cities with green legos as a child. Email him at ajonath1[at]ithaca[dot]edu.