“The Bin Laden movie” is a bracing, incendiary work of art, too hot for most Americans to handle

“The Bin Laden movie” is a bracing, incendiary work of art, too hot for most Americans to handle

The appropriate thing to first point out about the newest film from director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter/journalist Mark Boal is that it is nothing less than a masterpiece of filmmaking. Each of its many parts is entirely devoted to Bigelow’s vivid and bracing depiction of (allegedly) factual events.

The fact that Boal’s script synthesizes a decade’s worth of detective work and historical context into something comprehensible is itself an accomplishment. The fact that Jeremy Hindle’s production design – his first on a feature film – faithfully and intricately recreates dozens of international locations is above and beyond the requirement for most feature films. The fact that editors Dylan Tichenor and William Goldenberg were able to cut down Bigelow’s notoriously excessive amount of footage into a taut final product itself demands commendation.

These, in addition to the equally astonishing artistry from cinematographer Grieg Fraser to the peerless Jessica Chastain and her ensemble supporting cast, along with each aspect of the filmmaking process, contribute to a film of ferocious artistic integrity and omnipresent aesthetic success.

Moreover, each cog in the production machine has gone well beyond what was asked of them. Boal’s careful attention to sensitive details underscores the fact that his story is wholly involving: together with the momentum of Tichenor and Goldenberg’s editing, the story never allows the audience to let its guard down, lest they lose interest in the complicated chain of events on screen. Hindle and his crew erected a brick-by-brick replica of the Bin Laden compound in less than three months, in addition to painstaking work needed to construct situation rooms, office spaces, marketplaces, disaster zones, torture chambers and dusty military bases. Fraser shot the breathless late-night compound raid, an immaculate and revelatory sequence, in tricky night vision. Chastain made her portrayal of Maya’s obsessive, uncompromising nature – the character’s name itself an alias for a still-undercover agent Chastain has never met – more than just the defining feature of a faceted, believable character, and made a further statement on behalf of feminine strength and American psychology.

As its orchestrator, Bigelow was somehow able to pull each element of such a monstrous, timely epic together, at great personal risk: at the start of production, this was a true story less than a year old, one that had attracted the attention of just about every American citizen, as well as those around the world. Would it be a faithful account?

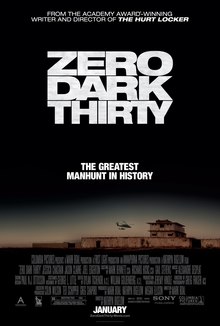

It is faithful, as far as we know, and for some people, its honesty is its condemnation. Since its wide release, Zero Dark Thirty is no longer a film so much as a point of voracious controversy and endless debate. Political pundits, CIA reps, Internet wackos, members of Congress, movie stars and the average American have gone round and round about the film’s ethical questionability: the incorporation of torture scenes, the speculative accuracy of the script, the use of languages other than Arabic in Pakistan locations, the opener using real 9/11 sound bites, et cetera, and on, and on. The boldness of the film has been met with astonishing backlash, almost on par with a cultural demerit or dressing-down.

Rather than defend Zero Dark Thirty’s integrity, something the filmmakers have accomplished in wake of its release, it is more productive to consider the meaning of such a reaction. Perhaps such scrutiny is a testament to the film’s titanic narrative force, its emotional rawness. However, the film is not meant to be a provocation, nor, thankfully, is it a piece of American cheerleading evoking the brash street parties on the eve of Bin Laden’s murder.

No. Zero Dark Thirty is, one could say, an American meditation; a preamble to the national understanding of what happened to us after 9/11. Its finer details evoke greater truths about how our national psyche changed so drastically after such trauma. We used extraordinarily cruel torture techniques, far beyond even what is shown in the film. We entered into a deadly war, on both military and cultural fronts. Years were spent on the hunt for one man, a pursuit fueled by hatred and, ultimately, executed with ferocious efficiency. When it was over, we rejoiced, made ecstatic by death and vengeance.

The echoes and parallels between this operation and that of al-Qaeda’s careful planning and execution of the attacks on 9/11 chill the soul. Did they not also rejoice at the deaths of Americans?

Zero Dark Thirty allows for this kind of reflection, and its obsessive attention to detail brings the bleeding edge of history to the American consciousness. In being forced to confront certain aspects of our immediate past, it seems, the American people respond with repulsion, suspicion and denial. Other great films that explore such raw history, like All The President’s Men and the astonishing United 93, tell tales of clearly defined good and evil: its protagonists are entirely virtuous, and by rejecting this convention, the plot of Zero Dark Thirty lacks an easy ethical foundation. Its ambiguity is its greatest feature, and, ultimately, what makes it so difficult to embrace. Indeed, for many Americans, it is difficult to swallow the film without choking on pride.

It may take years, but Zero Dark Thirty seems destined for a future of acclaim and understanding in lieu of an immediate intellectual and cultural success in the present. Hopefully, it will be recognized for what it truly is, free of controversy: a work of art at the highest level, a true American film, and a defining cultural benchmark of artistry and political consciousness. Perhaps, in the process, the American people will also come to understand who they are at least a little bit more.

Robert S. Hummel is the motherfucker that found this place, sir. Email him at rhummel1[at]ithaca[dot]edu.