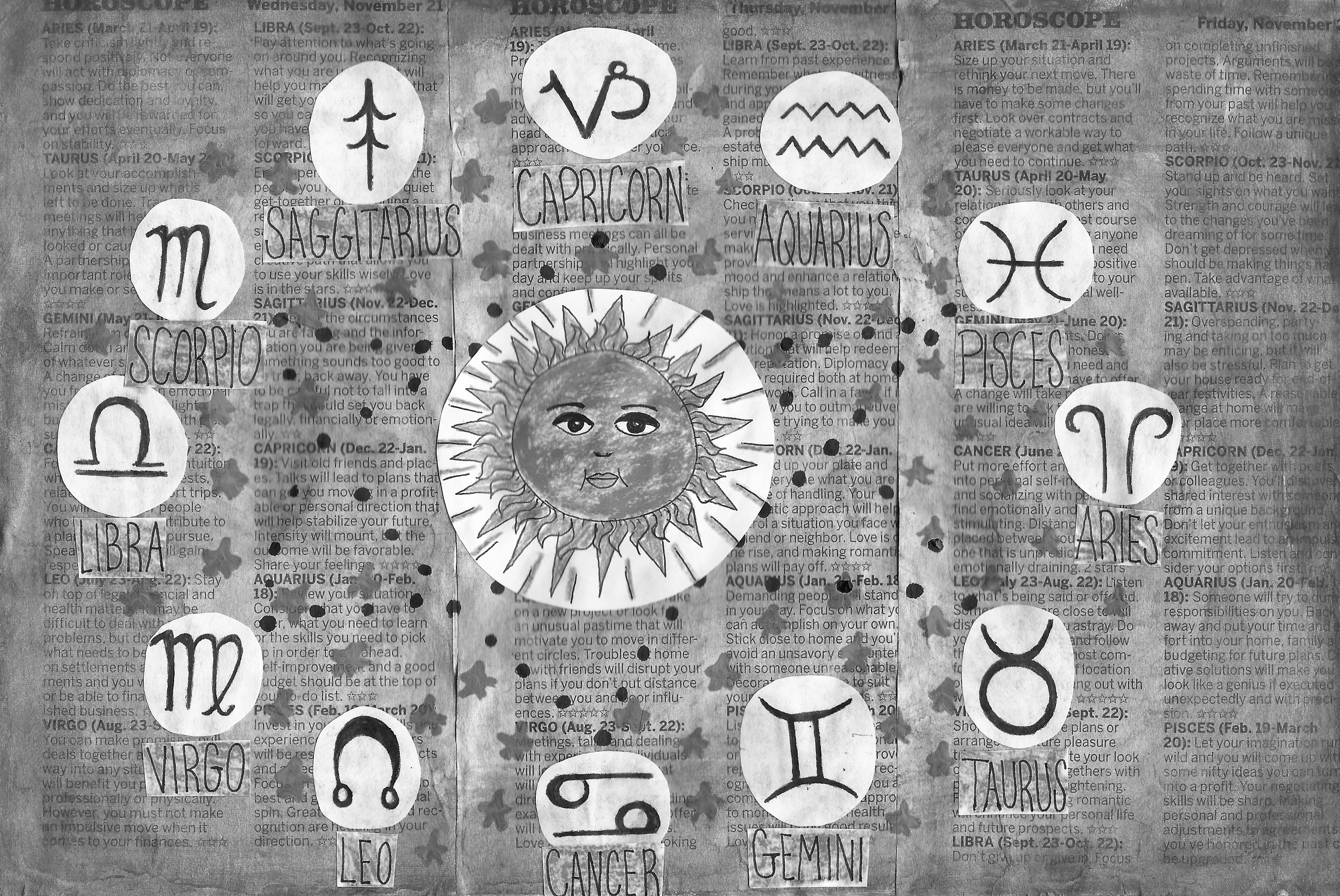

Image by Karissa Breuer

Is there a science behind our horoscopes?

When we have questions about our own lives, one solution is to look to the stars — or at least as far as the horoscope section in the newspaper. Something about the night sky makes us look for deeper meaning, and through our culture’s consideration of shooting stars, constellation legends, and zodiac signs, stars have long been much more than tiny specks of light against the sky. The motions of both the planets in our solar system and the stars within it are calculated, interpreted and connected to daily life on Earth through the controversial belief system known as astrology.

While astrology is sometimes inaccurately referred to as a “New Age” art, it is actually an ancient practice, with some records dating back to 1645 BC. Not to be confused with astronomy, the branch of science dealing with stars, planets, and their motions, astrology is a mystical and far less mainstream area of study. However, both fields have closely linked histories, and early astronomers often offered astrological predictions as well.

But how do the motions of the stars have anything to do with the events that affect us personally here on Earth? According to Linda Ruth, a professional astrologer from downtown Ithaca, that relationship is simpler and even closer than many people expect.

“Astrology is an ancient system based on ‘as above, so below,’” Ruth said, referencing the central astrological belief that the movements of stars and planets can reflect personal experiences on Earth. “What everyone is not aware of is that our bodies are made of stardust, and every planetary system has some planetary resonance within us. What I am trying to do is translate what the cosmic picture is, meaning the position of the stars and planets at any given moment and what that means to the individual psyche.”

In terms of the “above,” Ruth’s work involves analyzing the constant motion of stars and planets compared to one another, as well as their relationships to the individual. She explains that each person is born under a very specific celestial alignment, which becomes the client’s “natal chart,” based on the exact time, date and location of the person’s birth. While this means that the circumstances of each individual’s chart are fixed, she sees the chart’s predictions as more of a jumping-off point or set of possibilities than a single defined fate.

Some casual horoscope readers like the idea of not having total control over their fates.

“I don’t actively seek my horoscope, but when I see the word ‘Virgo,’ I can’t help but check it out,” Ithaca College junior Emma Martin said. “I guess maybe a small part of me wants to believe there’s some validity, a bit of insight into the month perhaps. The idea that fate is not in your own hands can be appealing.”

However, Ruth explains that the stars don’t provide one clear-cut prediction for any individual.

“For any given configuration of planetary bodies, there is an infinite number of ways that you’re going to interpret that,” Ruth said. “There’s a set of possibilities, and then there’s the observer, the personal psyche that’s interpreting it, and either they’re aligning with it or they’re fighting with it. How you’re going to interpret your individual horoscope is your choice.”

Still, as a mystical practice with minimal scientific support, many people are skeptical of astrology. It is commonly referred to as a pseudoscience, meaning that there is no significant evidence supporting its predictions and methodology.

Paul Thagard, Director of the Cognitive Science Program at the University of Waterloo in Canada, believes that modern astrology is misguided and used to explain patterns that would be better explained by psychology.

“Astrology is stagnant and hasn’t advanced in hundreds of years, and hasn’t taken into account why people have the personalities that they do,” Thagard said. “Associations between different features and the signs of the zodiac don’t really map onto anything that’s been tested empirically.” Thagard explained that the relationships identified by astrology tend to be based on similarities, and these correlations do not offer evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship.

However, when many people read their horoscopes or receive other personal information from astrology, they do feel that it resonates with their own experiences or personalities. Thagard said this resonance is often mistaken for evidence of the merit of the astrological prediction, though it really has more to do with psychology and the way we tend to process such predictions. He names some of the reasons why people believe in astrological predictions.

“One is that they aren’t aware of the alternatives — they don’t know anything about personality psychology. They don’t know that stars aren’t a very good explanation for aspects of their lives or that there are much better ones available. A lot of it, I think, is motivated interest, when you base conclusions not on facts, but on ways you’ve distorted the facts in accord with your goals,” Thagard said.

In relation to astrology, motivated interest is the human tendency to be more inclined to believe optimistic predictions, since the recipient would naturally want that information to be true. Thagard also believes that looser predictions, which are open to more flexible interpretations, are more likely to resonate with the individual, demonstrating the psychological tendency known as “cognitive bias.”

Overall, Thagard advises college students that astrological predictions are fit for entertainment purposes, but that taking them seriously is risky.

“If your level of astrology is opening up the newspaper and chuckling at it, there’s no harm in chuckling, in being amused by it, treating it as a kind of game. [But] students face a lot of important decisions. You have to figure out what you want to major in, what you want to do after graduation, and people are often beginning relationships… If people are making life decisions by taking into account the horoscopes of themselves or other people, they’re working with something that’s completely unreliable and they easily could be hurting their lives.”

Such a skeptical attitude is common, perhaps even mainstream, among students — but for true believers of astrology, no form of empirical evidence is needed to validate the connection they feel with such predictions. Through her experiences with both clients and outsiders, Ruth frequently encounters skeptics, and actually embraces their questioning attitudes.

“I think most people would be skeptical until they’ve had the experience,” Ruth said. “There are many people who … have some skepticism, and rather than having a long, philosophical debate about whether it should or shouldn’t work, I sit down with their charts and see if there’s anything meaningful … Hold onto your skepticism; it’s really intelligent to have skepticism until you have an experience.”

__________________________________

Karen Muller is a junior IMC major who accidentally registered for an astronomy course. Email her at kmuller1[at]ithaca.edu.