The reasoning behind general education requirements

Image by Kennis Kiu

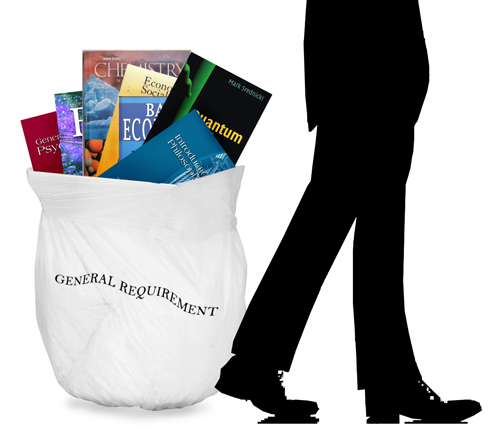

We log onto Homerconnect and search through all of the classes available, trying to find one that fits our desired schedule. First, we choose the classes for our majors, maybe a minor and use however many credits are left over for general education requirements. Maybe a math credit needs to be fulfilled, or a visual arts requirement, so we simply pick nothing too complex or time consuming, and happily rest assured.

General education requirements are meant to broaden our intellectual panorama, however, many of us simply see them as hurdles in the path to our degrees. We lack appreciation for the humanist intentions because of our job-oriented perceptions.

Yet maybe the humanities can teach us more than we think.

The humanities have been the mainstay of higher education since the foundation of universities. Focus shifted from the humanities to specialized tracks as the college population increased and job culture changed. Soon higher education’s purpose to enlighten the mind switched to create the ideal employee. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, this isn’t a bad thing, as students then become more marketable and have a higher job placement rate. What can the humanities do with such odds against it?

Educators have paved two paths for students to follow and try to answer the question of the humanities. One favors a means by which to reflect upon our humanity, and the other a pragmatic cooperation with professional tracks.

“There simply aren’t very good jobs for people who can’t solve and understand problems,” Park School of Communication’s Dean Diane Gayeski said. She describes how the humanities can help in such situations. Knowing historical or cultural perspectives provides students the ability to see past a single concept.

“You have to be able to think in so many different ways at the same time about the same thing,” Gayeski said. “You have to look at a problem and say ‘O.k., I understand this from a cultural/diversity standpoint [or] I understand this from a historical viewpoint.’”

Gayeski said focusing solely on one’s field leaves students without the means to apply it to an area. Yes, you mastered the skill, but what will you do with it? Here, knowing about history or art or literature can provide students with something to apply to their craft.

Massachusetts Commissioner of Higher Education, Richard Freeland, furthers this idea and binds them.

“I would encourage a college to think about interdisciplinary freshmen seminars that team faculty from different fields, especially faculty from professional and liberal arts subjects,” Freeland said. “These faculties would develop coursework and curricula so that both the liberal arts perspective and professional perspective can add value to the understanding of a particular problem or a particular situation.”

Practicality can provide students with a reassurance that they are getting their money’s worth while also partaking in the materialist culture they live in. Yet, the purpose of the humanities and liberal arts education expands further than just applicability.

“We, as a society, have certain sorts of things we focus on,” points out Humanities and Sciences Dean Leslie Lewis. “If we are focusing on material ways, then our children are going to focus on material ways. The humanities’ question is really simple: So you want to go to college to get a good job, why do you want to get a good job? What’s the point?”

As students, some of us seldom ask these questions. Under torrents of class work, internships and extracurricular activities, we continue to drown and cannot see past our set goals into the larger picture. With this, we disregard how college helps us open ourselves to critical thinking with our gen eds.

“A typical way of thinking about general education requirements is distribution requirements. That is a little bit of this, a little bit of that, broadly across the liberal arts. And that’s, in some way, what we have now at Ithaca College,” Lewis said.

The IC 20/20 plan means to remedy this disparity by integrating gen eds into a themes and perspective model that allows students to pick a theme and study it from different academic perspectives. It encourages students to appreciating gen eds and explore how they can enrich their education.

“If you want to answer those really big questions that have to do really with fundamentally the meaning of life, you need the humanities. You really need to know where other people have gone with those questions and those answers,” Lewis said.

She continued to explain how humanity is figuring out the meaning of life, and that the humanities help us in this journey.

“What’s the point? That’s not a rhetorical question. That’s a real question, what’s the point of your life?” Lewis said.

“Certainly everybody has thought beyond just that job and that paycheck, so what is it that you want to do? What kind of mark do you want to make on the world? Why are you alive? It’s really as fundamental as that, I think. It’s a scary set of questions. It’s a lot easier to say, ‘I just want to get a good job and make a lot of money.’”

Such questions undermine the world we live in and, perhaps, have led to our collective dismissal of the humanities. Gen eds can help students shift toward living for the sake of exploring and understanding life rather than living to reach a goal. Because if we achieve our goal and have no deeper understanding of the world, we’ll find nothing else.

Rodrigo Ugarte is a junior writing major whose heart and soul belongs to the humanities and sciences. Email him at rugarte1@ithaca.edu.