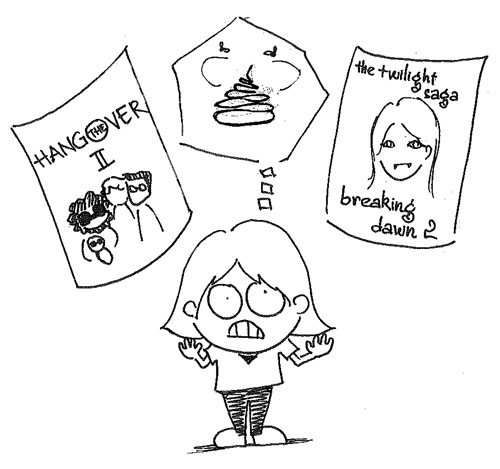

When and why did the movie industry become so desperate?

Image by Kieu Anh

Cinema has always been a medium that has astounded and amazed people of all generations and backgrounds. The expression “the magic of cinema” is not too far off from the truth. Sadly, it will take more than applause and pixie dust to keep it going. In a world in which a film like Twilight can break box office records, there is little hope that the “magic” will last much longer.

Maybe it’s just the changing times, but it seems as though for the last ten years, the theaters have been filled with crap, and the rare worthwhile movie – usually coming from the same few directors like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese or Christopher Nolan, who have been making quality films since before movies were reduced to big budget shit-shows. Now films have begun to deteriorate in quality (once again, I give you Twilight). So, has this generation just been the downfall of high culture? Are films forever doomed to be reduced to stale close-ups of angsty teenagers and million-dollar action sequences “just because”? The future of cinema seems pretty grim.

Not to mention, our society is slowly getting dumber. Not scientifically, (obviously) but culturally. We either do not have the time to engage ourselves in conversations about film and art, or we are simply not interested. This very well may be due to the decline of quality entertainment options. It seems as though film has one specific target audience in mind: the teenage demographic. It is almost as if studios are forgetting about older generations, or they simply do not care about people who maybe want something more thought-provoking. Steven Ginsberg, a writer, film blogger and professor at Ithaca College’s Los Angeles Program, says that studios would, in fact, consider this a wide target audience.

“What I think they would say to you is that it is broad in that teenage boys and girls are the core movie-going audience. … they don’t think people over 50 are going to go to the movies with any consistency. But I believe they will if there’s something they really want to see,” Ginsberg said.

So the problem now becomes that films are being made not for a wide variety of people, but for the group of people who the studios think are going to the movies most often — the same people who find entertainment in Jersey boys on steroids going tanning, and 16-year-olds getting pregnant. It seems to be a vicious cycle.

Ginsberg went on to say that studios don’t care that perhaps the older generation wouldn’t want to see a movie like Transformers or Twilight, because they’ll put out a film like The King’s Speech or The Artist for them at the end of the year. These movies will receive the acclaim from the Academy of Motion Pictures for Old White Men, but they will not be the summer blockbusters that have people dressed up and waiting for the midnight premiere. Imagine dressing up as King George IV or Margaret Thatcher and lining up at the mall. Chances are it won’t have the same effect as dousing oneself in glitter as a Cullen or waving a tree branch muttering “Crucio!” to anyone who dares cut the line.

Holly Van Buren, who co-teaches a class dedicated to learning about Hollywood and American Film at Ithaca College, says that the ability to cross mediums is what makes studios so interested in making a film, and what, in turn, makes people obsess over them.

“Once we had George Lucas create Star Wars, it’s like a lightbulb went off and [the studios said] ‘If we can make movies that we can make toys for and Happy Meals and theme park rides, we can make a ton of money,’” Van Buren said.

This trend is clearly visible in recent years. Out of the top 10 grossing films of 2011, only one was not a sequel (The Smurfs). Every one of the top 10 films has so many components that can be exploited through different mediums — whether it’s action figures and toys, a movie soundtrack, or even a multi-million dollar theme park.

“What the studios want is for the movies to become a cultural phenomenon,” Ginsberg says. “They want it to become more than the movie [because] they are pre-sold commodities. If you already have a story that was really successful (i.e. The Hunger Games), the studios think: ‘Why not? Why wouldn’t this work as a movie?’ and they also have a pre-sold audience. So, why not do that rather than take a chance on some writer [who] sat in a room and wrote an original screenplay — because how do they know anyone is going to be interested in it?”

This trend was also evident in 2009, when James Cameron’s mega-hit Avatar became the first film to gross over two billion dollars. Avatar is essentially a mash-up of Pocahontas and Fern Gully, and it earned three hundred million dollars. In the 1990s, only two of the top 10 grossing films were sequels: Toy Story 2 and Star Wars: Episode I.

So, what’s changed? Perhaps it was the constant need for something familiar. Or maybe Hollywood has just officially run out of ideas. It seems as though all of our childhood shows and cartoons are either being made into some over-hyped extravaganza made by Michael “my movies have officially become clichés of themselves” Bay, or a painfully dragged-out CGI. Besides that, some of the most classic movies ever made are in the works for remakes, including 2000’s American Psycho. That’s right. According to gossip guru Perez Hilton and later confirmed by The Washington Post, a film made just less than twelve years ago is getting a reboot.

This is not to say all reboots should be condemned to the $2.99 bin at the local carwash. Familiarity can work sometimes when it’s not a direct copy (see — or rather spare yourself the pain of seeing — the 1998 Vince Vaughn remake of Psycho). While America does not need a reboot of Annie, The Birds, or War Games, there is some sense to making a film such as Tim Burton’s campy re-telling of the cult TV series Dark Shadows. After all, Scarface was a remake. There must be a reason for the film to be remade, with motivations other than the convenience of not having to be creative or original. There’s a fine line.

Case in point: the new Amazing Spider Man film. Some may argue valiantly against the reboot coming out this year, but from the perspective of a self-proclaimed Spider Man aficionado, it makes more sense then the absurdity that was Spider Man 3. The original comic books spawned several spin-offs, some taking place in universes other than the original, telling alternate stories. The new film still keeps to the original story — however, this film offers more depth to each character and more of a reason to root for the web-slinger. It’s not so much a reboot as a different perspective. Also, Kirstin Dunst’s whiney Mary Jane is replaced by Emma Stone as Gwen Stacey, which we can all be relieved about. Oh, and maybe it will restore some of the bad-assness that the musical version, Turn Off the Dark, jazz-squared out of the franchise.

Luckily, there may be hope for the future of film, as grim as it may appear. After all — isn’t it always darkest before the dawn? Perhaps a new generation of film students will swoop in and save the day. Van Buren offers us a glimpse of hope, even for the present.

“There are still good films being made,” she said. “You just have to find them.”

Rachel Maus is a freshman cinema and photography major who refuses to see Titanic in 3D. Email her at rmaus1[at]ithaca[dot]edu.