Society’s normalization of divorce

Image by Clara Goldman

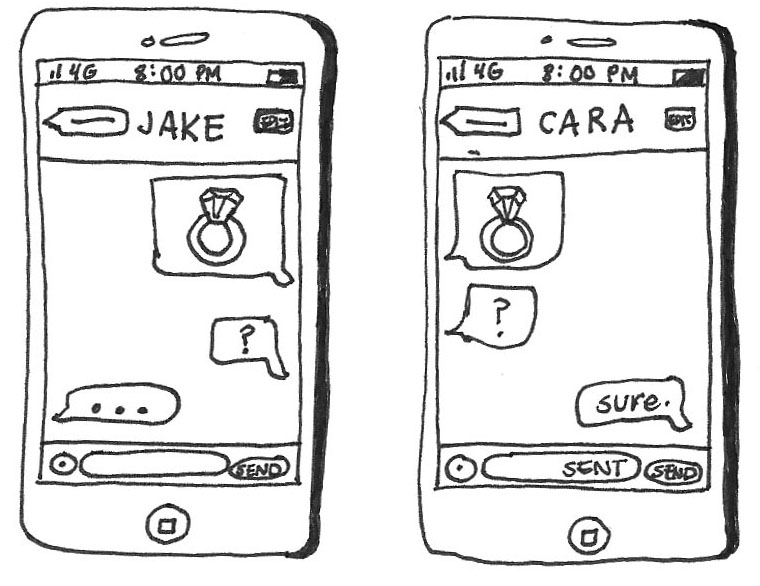

For something that is so prevalent and dynamic in our culture, the portrayal of marriage and divorce is very generalized. Marriage has often been romanticized into an ideal of two people who are head-over-heels for each other that go to their nearest house of worship, recite their vows and ride off into the sunset in their car with aluminum cans tied to the back. In contrast, divorce is typically depicted as a violent, hateful mess initiated by adultery and ending in emotional scarring for the children who are inevitably caught in the middle.

Sarah* was married for 15 years before divorcing her ex-husband in 2001. Though the divorce was initiated by an extramarital affair on his part, she feels the way the media represents marriage and divorce is inaccurate.

“I think that any movie that shows marriage as fun and happy all the time is incorrect,” Sarah said. “It’s much more emotionally difficult than the media portrays it as.”

Regardless of whether these idealizations were ever true or not, society has changed — both in the way marriage and divorce are experienced and in their frequencies. According to National Affairs, about 50 percent of adults are married, and approximately 40 percent of marriages today end in divorce. However, the changes in both marriage and divorce rates are not the result of the trend of expendability in our society, as celebrity marriages and divorces may suggest. Rather, they reflect the needs and wants of people today.

Krista Payne, an analyst for the National Center for Family and Marriage Research out of Bowling Green State University, said that marriage rates have decreased for any number of reasons, though cohabitation and the economy are likely the largest factors.

“Cohabitation has become so much more normative,” Payne said. “The vast majority of marriages are preceded by cohabitation now, and there are people that are choosing to cohabit and they forgo marriage altogether.” She also cited economic conditions as a factor in the decrease, since many couples do not want to marry until they are financially stable.

Marilyn Westlake, an attorney who focuses on divorce mediation, said divorces were not commonplace in the past due to societal and religious taboos, as well as tangles in the law. In the past, New York state law said that assets belonged only to the person whose name was on it, so a person had no right to anything his or her spouse had the title for. This led to messy divorce fights, and the state changed the law to ‘equitable distribution,’ where each spouse in a divorce has equal right to the value of the assets.

“Now, the titled spouse doesn’t have the upper hand,” Westlake said. “I think that was a huge change that allows people to get divorced who otherwise might have stayed married because they didn’t know what they had and they had no rights.”

Conservative and religious groups often denounce the changes in both because they feel it destroys the sanctity of marriage. However, Rev. David Grimm, minister of the First Unitarian Society of Ithaca, says that there is a distinction between the religious marriage and the legal marriage, so the religiosity of marriage is dependent not on society as a whole but rather the people directly involved.

“Technically, a marriage is a legal agreement that two people promise each other, sign, give their vows, exchange something of worth,” Grimm said. “There has to be an officiate of the state there to witness it and two other people there to witness it, and that’s all that’s required.”

The religious connotation of marriage, Grimm said, came from an interpretation of the Bible that Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden was the first marriage and is therefore the model. Marriage, then, is a religious commitment in which “you’re promising in front of God to be the best partner for each other and ‘‘til death do you part.’” He said that the magnitude of this commitment is so important that “you’d have this ceremony to show that this is a sacred, sacred thing.”

Grimm also said that, in many congregations, divorce is not always seen as a sin. Instead, they recognize that not all relationships work and staring anew is a good thing.

“I know that within Unitarian Universalist congregations, not all of them, but some of them actually had rituals that ended the marriage,” Grimm said. He said that the concern was finding a way to ending a marriage without a lot of anger and suffering, so a ceremony was developed that allowed people to make a clean break.

After 11 years, Sarah has maintained a good relationship with her ex-husband, particularly through the “strong co-parenting” of their children despite the separation.

“I would say he’s an awesome ex-husband,” she said.

Maybe then, divorce should not been seen as the throwing away of a marriage, but as the repurposing of a life: redefining relationships for something better for both individuals involved.

*Name has been changed to protect anonymity.

Amanda Hutchinson is a freshman journalism major who can’t wait to ride off in a car with the aluminum cans tied to the back. Email her at ahutchi2[at]ithaca[dot]edu.