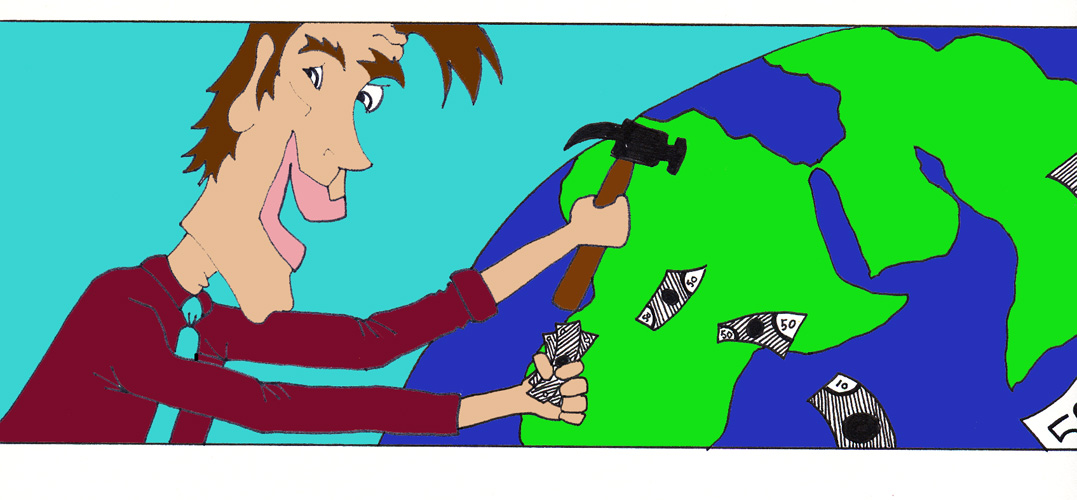

How understanding the complexities of charity expose its harm

Image by Daniel Sitts

Charity takes shape in multiple forms. From humanitarian aid shipped out to Haiti in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake to community service in Tompkins County, we have a cultural propensity to give, help, serve and donate. Charity often represents the ultimate form of compassion. But what if the way in which we construct charity is problematic? In order to better grasp the consequences of charity, we should try to understand how it happens as a process.

First and foremost, we should consider what each of us feels when engaging in charity. To begin such work, we must try to accomplish two things: One, to assess the feelings and reactions of those receiving charity as thoroughly as possible without speaking for them, or assuming we can figure it out easily, and two, to explore our own motivations and the degree to which charity validates them. True, our motivations and the experiences of others cannot be ascertained without hard work and self-reflection. But if we constantly attempt to critique ourselves, we will get a more complex grasp of charity as it unfolds as a political transaction.

When addressing the first endeavor, we start to think about the extent to which people receiving charity actually resent it. Because we live in a world in which the number of people living in poverty without adequate access to resources, jobs and a healthy living environment is incredible in scope and size, we foolishly assume it is only the acquisition of stuff that improves a charity recipient’s personal satisfaction and quality of life. In other words, if they aren’t living in a house, they hate that they don’t have a house. Therefore, we build them a house and their lives are less shitty.

To a certain extent, people probably do appreciate having a roof over their head. I have never had to know what it’s like without one, so I must not trivialize the relief of obtaining shelter. Plus, I have to recognize that building a house requires considerably more effort and personal confrontation than, say, checking a box on a donation card. Still, by living in poverty, people who receive charity are not just recipients of an item previously denied to them; they are also reminded of the culture in which they live. They don’t just need a house to improve the condition of their lives; this goes beyond the resources themselves. Through charitable action, people continue to remain dependent on the financial power of others, lack fundamental economic rights that would otherwise entitle them to things like affordable housing and are, at the end of the day, a project for someone, a temporary moment of aid.

Thus, we need to look back at the motivation of the “helper,” which often is the “we” I speak of. We probably recognize the widening gaps in wealth in our classes and conversations. This “we” typically (I stress “typically”) consists of white, middle-class college students with good intentions and extra time. Perhaps we are compelled by images of genocide and famine, and hope we can make a seemingly horrifying world better by tackling these issues with our money and resources.

Unfortunately, by giving to charity, we tend to undermine both our own complicity in the systems that perpetuate inequality and the tension a person receiving charity faces. We probably don’t ponder the humiliating process charity means for many people. Perhaps we only donate to feel better about ourselves, or to avoid the way in which we have benefited from an unequal, unjust world. As a nation that relies on cheap labor and profitable warzones to fund its oil consumption, inexpensive jeans and smart phones, it becomes almost necessary to avoid the difficulties of this contradiction by simply donating or giving away old items and calling it a day. We pretend our lives are mutually exclusive from the poverty we seek to combat. I hope we can start to alter this line of thinking.

To be fair, plenty of students engage in charity work and recognize that it is a hotly contested process without inherent goodness. But such students do not likely comprise the majority of the population that conflates “charity” with “help.” In many cases, charity is not help; it’s harm. Or at least, it’s hindering the process toward liberation. Charity is not unequivocally good or universally accepted by its recipients. So before we continue to associate it with high ethical standards and go about our days, we might want to remind ourselves how complicated it really is and think about our own involvement.

Chris Zivalich is a senior journalism major who will still help you when you’re down. Email him at czivali1[at]ithaca[dot]edu.