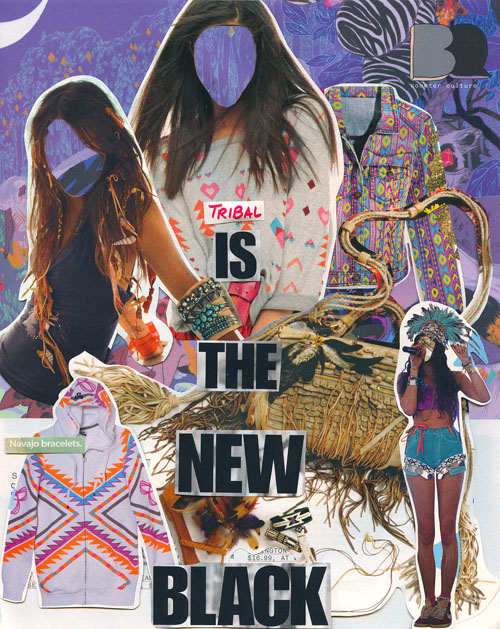

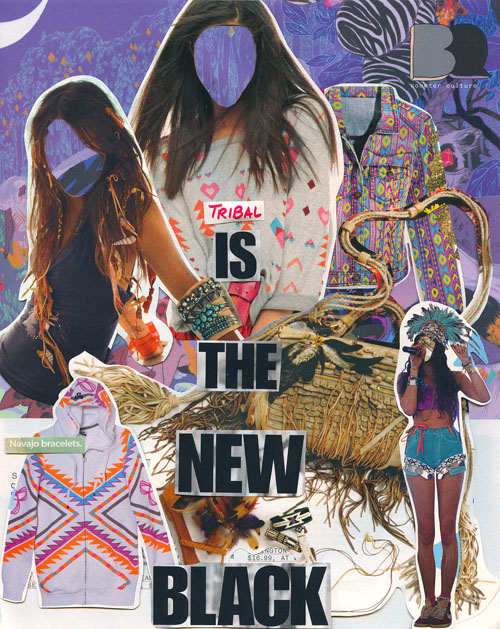

Image by Jenni Zellner

Image by Jenni Zellner

Hipster outfitters with unsavory intentions

A step through the door transports you to an exotic land. Feathers sway in the breeze before the door slams. Entranced by the howling wolves, the geometric bird prints, you cannot help but run your fingers through every clinking bead. You smile at the copper tint of your fingertips, the dream catchers and moccasins freshly dyed. You can practically smell the dry Arizona air and hear the coyote’s moon song.

And to think, you only came in for a mustache flask and a $68 ironic t-shirt.

Urban Outfitters thrives on the demands of the modern, college-age nonconformist. Styled to emulate your local thrift store, Urban Outfitters prides itself on feigned authenticity. The clothes look worn, the design brands sound humble, and even some pieces are made with recycled materials.

The trend of vintage clothing supports eco-friendly lifestyles, small businesses and frugality. However, “starving-artist chic” has created a phenomenon of worn, thrifty clothing that is making appearances in chain stores with brand-name prices. There’s an increased demand for fashion with even humbler beginnings than the Salvation Army. The must-have in the garment industry is now tribal.

Last fall, Sasha Houston Brown, a member of the Santee Sioux Nation, wrote a letter of outrage to Urban Outfitters. Brown called their collections “distasteful,” “racially demeaning” and “a violation of federal law.”

“I take personal offense to the blatant racism and perverted cultural appropriation your store features this season as fashion,” she said.

The following week, Urban Outfitters removed the word “Navajo” from the names of more than twenty products, including the “Staring at Stars Strapless Navajo Dress” and “Navajo Hipster Panty.” Urban Outfitters’ spokesperson Ed Looram said the company received a cease and desist order from the Navajo Nation a week prior — which makes it seem like Urban Outfitters didn’t remove the “Navajo” stamp based on consumer outrage, but on threatened legal action.

A local member of the Navajo Nation was far from surprised.

“There they go again,” Hollie Kulago, professor of Native American studies at Ithaca College said. “Exploiting our people, our culture, our land. It’s just another thing thrown on the pile.” In a good-humored tone, she added:

“[Native Americans] laugh because we’ve seen it all before. You’d think they’d learn by now.”

And yet the cycle continues.

In every generation’s attempt to be more authentic than the last, trends stem from harsher, rawer environments, making the fashion of developing communities in vogue.

Take a stroll through a popular retail store. Stuffed on the racks of Forever 21 and H&M are pieces labeled “Aztec,” “Ecote,” “South-Western” and “African.” To this day, Free People and Anthropologie market “Navajo” jewelry and scarves. The company that owns these two retail shops URBN Inc, also owns Urban Outfitters.

And last fall’s tribal mania did not die a bargain bin death this spring.

At this year’s New York Fashion Week, designers such as Diane Von Furstenberg, Zac Posen and Tory Burch kept the exploitive flame burning for Spring 2012. The must-have accessories of the season, called “tribal chic” by Harper’s Bazaar, are defined by the use of ethnic and tribal prints and dyes.

Donna Karan’s collection includes a number of exotic pieces, including a “small cluster necklace” made of woven chord and orange, shell-like spikes. The Nieman Marcus website assured the necklace would “add a cultured, cool edge to anything you pair it with.” All for just $995. Michael Kor’s collection, of “memories of Africa” was described as “an exciting journey into a faraway wilderness.”

Rodarte sported models covered with black tribal tattoos.

Why don’t we just wear loin cloths? That would be, like, so tribal-chic! What’s next? Clothing lines inspired by the homeless? Mugatu’s Derelicte fashion line may not be too far off.

What sparked this tribal fad? Are we subconsciously working through the guilt bestowed by our forefather’s colonization? Perhaps the inappropriate use of cultures’ traditions is an indirect glorification.

But not all cultural appropriation has been negative. Some has actually benefitted those who were exploited in the past. Musician Paul Simon used indigenous croak sounds from the people of Lesotho in his album Graceland. A past inhabitant and avid studier of Lesotho and its people, Associate Anthropology Professor David Turkon commented on Graceland’s impact.

“Simon came under severe criticism for exploiting their music,” he said. “But he raised awareness of a situation there. All of a sudden the bands he recorded, like Lady Smith Black Mambazo, were gaining notoriety and were able to express their causes.” But Turkon doubted that the fashion industry could accomplish what music could.

Does this trend promote awareness or ignorant misconceptions?

The missing piece to this cultural puzzle is collaboration. Ten Thousand Villages, a shop down in the Commons, is an example of a storethat sells accessible, authentic trinkets, kitchenware, candles and clothing. A founding member of the World Fair Trade Organization, the company has spent more than 60 years cultivating trade relationships from artisans around the globe. This form of “tribal-chic” actually supports the cultures that inspire recent trends.

I advocate celebrating the beauties found abroad and in our own country, but let’s make sure they are cool with it first.

Mimi Reynolds is a sophomore journalism major who knows there’s a lot more to life than being really, really, ridiculously good looking. Email her at areynol2[at]ithaca.edu.